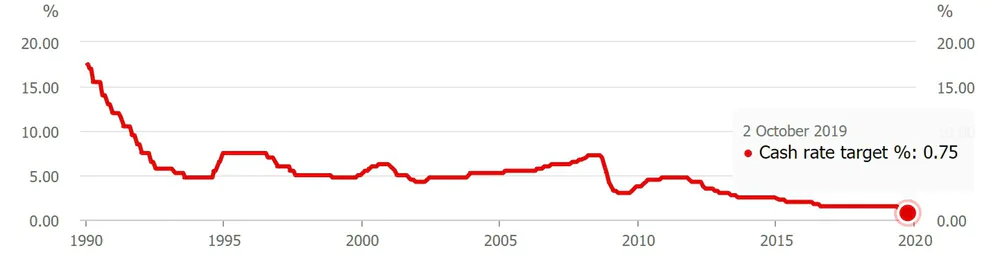

The Cash Rate Is at Record Lows, But Don’t Think For a Second the Reserve Bank Has Finished Cutting It

Anyone who thought that with the Reserve Bank’s cash rate now close to zero, its run of interest rate cuts was over, needs only to read the last sentence of Governor Philip Lowe’s announcement after Tuesday’s cut:

The Board will continue to monitor developments, including in the labour market, and is prepared to ease monetary policy further if needed to support sustainable growth in the economy, full employment and the achievement of the inflation target over time.

For the longest time, the run of cuts was over.

Lowe’s immediate predecessor, Glenn Stevens, cut the cash rate to a record low of 1.5 per cent in August 2016 as something of a “parting gift”, allowing Lowe to take over and keep it steady, unchanged for a record 34 months.

For most of those three years he made it clear the rate was unlikely to fall further. Six times he said the next move in rates was likely to be up, “rather than down”, pointing to rate increases overseas and progress on jobs and returning Australia’s unusually low inflation rate to his target band.

By February this year he was backtracking. Although it wasn’t apparent in the published figures, the unemployment rate was about to begin climbing. Wage growth had been far weaker than forecast, inflation showed no sign of returning to the centre of his target band, and forecasts for global growth were falling.

More importantly, consumer spending, which accounts for six in every ten dollars spent in Australia, was extraordinarily weak, growing at less than half the usual rate, as households “responded to this extended period of weaker income growth by progressively downgrading their spending plans”.

The probabilities of next move being up and down had become “more evenly balanced”.

Read more: RBA update: Governor Lowe points to even lower rates

Two weeks after the May election he cut the cash rate, then cut it again, taking it to a new record low of 1 per cent, anticipated by only two of the 19 economists surveyed by The Conversation just six months earlier.

The extra cut announced on Tuesday is because the last two didn’t do enough.

House prices have begun to move up (as would be expected with lower rates) but borrowing is growing only slowly, and home building is weak. The Australian dollar is low (in part because of the lower rates), which should help make Australian businesses competitive, but they are not keen to borrow.

Since the last Reserve Bank board meeting we have learned that economic growth is shockingly low, just 1.4 per cent over the past year, the weakest since the global financial crisis. Household spending is barely keeping pace with population growth.

Lowe would like to believe the economy has reached “a gentle turning point”. He told a community dinner in Melbourne on Tuesday night the board thinks it might have.

There are a number of factors that are supporting this outlook. These include the low level of interest rates, the recent tax cuts, ongoing spending on infrastructure, signs of stabilisation in some established housing markets, and a brighter outlook for the resources sector.

But they will need help. The bank believes the economy is capable of producing an unemployment rate of 4.5 per cent. Instead it has been climbing, to 5.3 per cent.

How the cuts will help

The cash rate is determined by the rate the Reserve Bank pays banks who deposit with it overnight. It drives almost every other rate, including the rates banks pay retail depositors, which help determine their cost of lending.

They don’t have to cut their mortgage and business rates in line with cuts in the Reserve Bank cash rate, but they usually do.

The big banks played a game of chicken yesterday, each waiting for the other to move. The Commonwealth Bank moved first, offering just 0.13 of the 0.25 points, followed by the National Australia Bank, which offered 0.15 points.

The real action is in the discounted rates that target borrowers for whom they matter. Before Tuesday they averaged 3.46 per cent. Some were much lower. HSBC Australia wanted just 3.17 per cent. If it passes on Tuesday’s cut in full it will charge only 2.92 per cent, offering the first Australian mortgage rate in history beginning with the number “2”.

There’s every reason to believe the cuts will help. Even if Australians don’t borrow more to buy houses, they will be able to use the historically cheap credit embodied in their house loans to buy other things, such as solar panels whose payoff period will have shortened dramatically.

Since June many mortgage-holders will have saved A$150 on monthly payments.

Sure, confidence and decent wage growth would help, but given how indebted many Australians are, low mortgage rates will do quite a bit on their own.

Why they’ll continue

Governor Lowe made it clear on Tuesday that they will have to stay low for “an extended period”. A signed agreement with the treasurer requires him to keep them low until unemployment falls and inflation and economic growth return to return to normal levels.

He would like the government to help by boosting spending. He often mentions spending on infrastructure. But his employment contract requires him to use the cards he has been dealt. If the economy is weak, he is required to boost it using the instruments he has.

Read more: Below zero is ‘reverse’. How the Reserve Bank would make quantitative easing work

That’s why he says he is prepared “to ease monetary policy further”.

If needed, he’ll do it as soon as next month, cutting the cash rate to 0.5 per cent. If more is needed beyond that, he will get ready to use so-called unconventional measures of the kind being used overseas, buying government and corporate bonds in order to force even more money into Australian’s hands.

There’s no reason to believe that the tools he has won’t work, and every reason to believe he’ll keep using them.

Author

Peter Martin, Visiting Fellow, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.