Nine Iconic Examples of Modernist Architecture

For devotees of mid-century modernism, 15-25 February is the time of the year, with Palm Spring's Modernism Week officially kicking off in a celebration of mid-century architecture and design.

Modernism first emerged in the early 20th century and its credo—or cliché, depending on who you ask—"form follows function", played a critical part in the evolution of the world's major cities.

In celebration of the modernist architectural movement, The Urban Developer reached out to Jack Hale and Eddy Rhead, the publishers of British-based The Modernist magazine and asked them to provide us with a rundown of some of their favourite modernist architecture from around the world.

Park Hill – Social Housing (Sheffield, UK)

Architect – Jack Lynn and Ivor Smith

The programme of house building in the city of Sheffield in the 1950s and '60s attracted the attention of the world. Delegations from as far away as the Soviet Union came to the city to see how it was handling the huge job of rehousing its residents.

Park Hill was one of the largest of these and adopted the deck access "walkways in the sky" approach. In 1998 it was Grade II-listed in recognition of its place in architectural and social history and as such became the largest Grade II-listed building in the UK.

It is currently undergoing refurbishment to turn it into private housing.

Coventry Cathedral – Ecclesiastical (Coventry, UK)

Post-war reconstruction in Britain's cities was as much an ideological process as it was a physical one. Large scale destruction of city centres gave town planners the opportunity for a "blank sheet" when rebuilding and Coventry, heavily bombed in World War II, was perhaps the best example.

The new cathedral, which incorporated the war damaged ruins of its predecessor, was a triumph not only of Modernist architecture but served as a beacon of reconstruction and reconciliation in an uncertain post war Britain.

Coventry Cathedral is an almost peerless building for its mix of traditional craft, beautiful artworks and cutting edge design.

Brasilia – Government and Civic (Brazil)

The decision to move the capital of Brazil to an area of impenetrable rain forest was an audacious and risky one. Luckily for Brazil it had one of the worlds greatest architects in Oscar Niemeyer and he was responsible for designing many of the new capital's major buildings.

Whether the city works, 50 years on, as a good place to live and prosper is a matter of opinion but as a collection of outstanding Modernist architecture it is second to none.

Architectural highlights include the hyperboloid Cathedral of Brasilia, The Congress of Brazil building and Palácio da Alvorada – the President's residence – all in Niemeyer's signature seductive, almost sensuous, style.

Sydney Opera House – Cultural (Sydney, Australia)

The word "iconic" is much overused but when one a city has a building that comes to optimise that city and is instantly recognisable the world over its fair to say it has achieved iconic status.

Sydney Opera House is such a building. A long, often controversial, design and build process was perhaps inevitable from such a radical and experimental design.

Engineering challenges of the design led to innovative solutions and only contribute to its beautiful mystique. Not only an important architectural statement Sydney Opera House showed other cities around the world of the importance of large scale cultural projects and their role in defining a cities image.

Munich Olympic Park and Athlete Village – Housing (Germany)

The 1972 Munich Olympics were a chance for Germany to show the world that they were a progressive, liberal and modern nation.

The structures for the sporting venues were designed by Frei Otto and, working within the undulating landscape of the park, he adopted a sinuous plexiglass canopy, held up by pylons and steel cables.

At once hi-tech and yet somehow organic, the structures look as radical today as they did 45 years ago. The adjoining Olympic village is a mix of ziggurat duplexes, low level maisonettes and tall towers.

Through careful planning and good management the village still retains a utopian air and proves that bold and dynamic Modernist architecture need not relegate its inhabitants as secondary to architectural vision.

Sirius – Housing (Sydney, Australia)

Sirius, an apartment block in Sydney, has gained international exposure because it provides an interesting bellwether of where we are with regard to recognition and appreciation of brutalist architecture but also shines a spotlight on wider social issues regarding redevelopment and social housing.

Sirius shatters some of the myths regarding Brutalist architecture in so much that given a mixed demographic of tenants and thoughtful design, Brutalist social housing need not be the dystopian nightmare many imagine it to be.

Sirius's location, one of its biggest assets, has proved its downfall. It is now prime real estate and potentially lucrative for the local government, who plan to empty the building, demolish Sirius and sell the land for private development. The residents who have happily lived there for three decades seem to factor little in this decision.

Seagram Tower – Commercial (New York, USA)

It is said that imitation is the highest form of flattery and as such the Seagram Building must have been constantly blushing since its completion in 1958.

It set the benchmark for almost every commercial office block that has come in its its wake and whilst it is often copied it has rarely been bettered.

To have an almost unlimited budget, a very understanding client and the genius of Mies van der Rohe obviously helps matters but the attention to detail, the use of high quality materials and the peerless Miesean "Less is More" design has ensured the Seagram Building is as influential and thrilling today as it was 60 years ago.

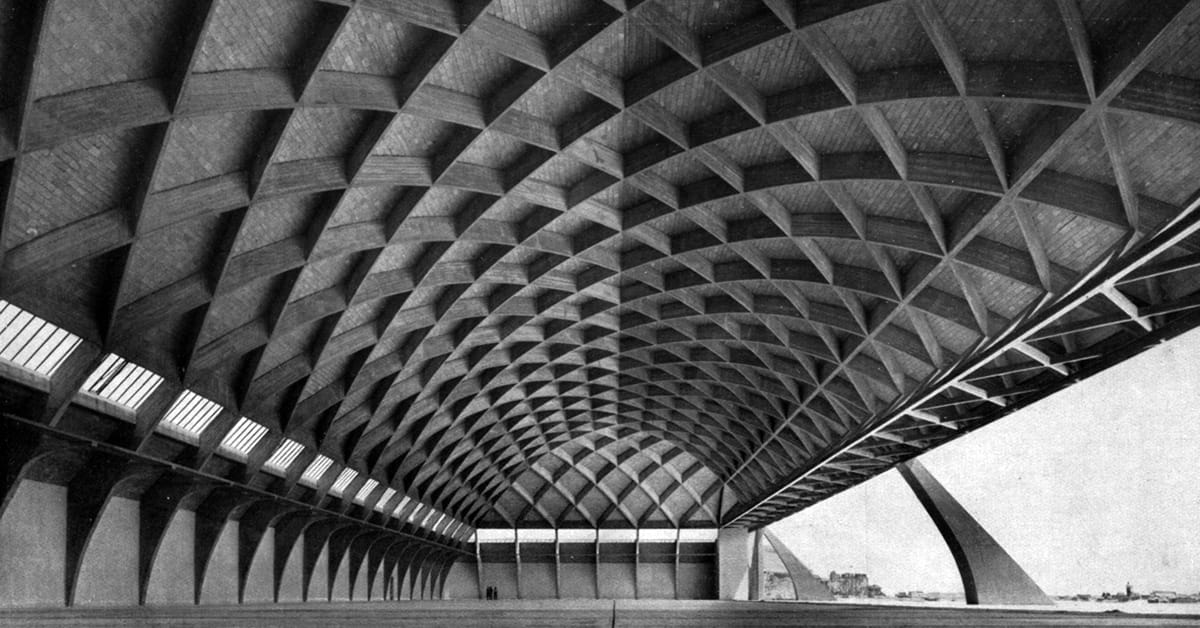

Aircraft hangars – Industrial (Italy)

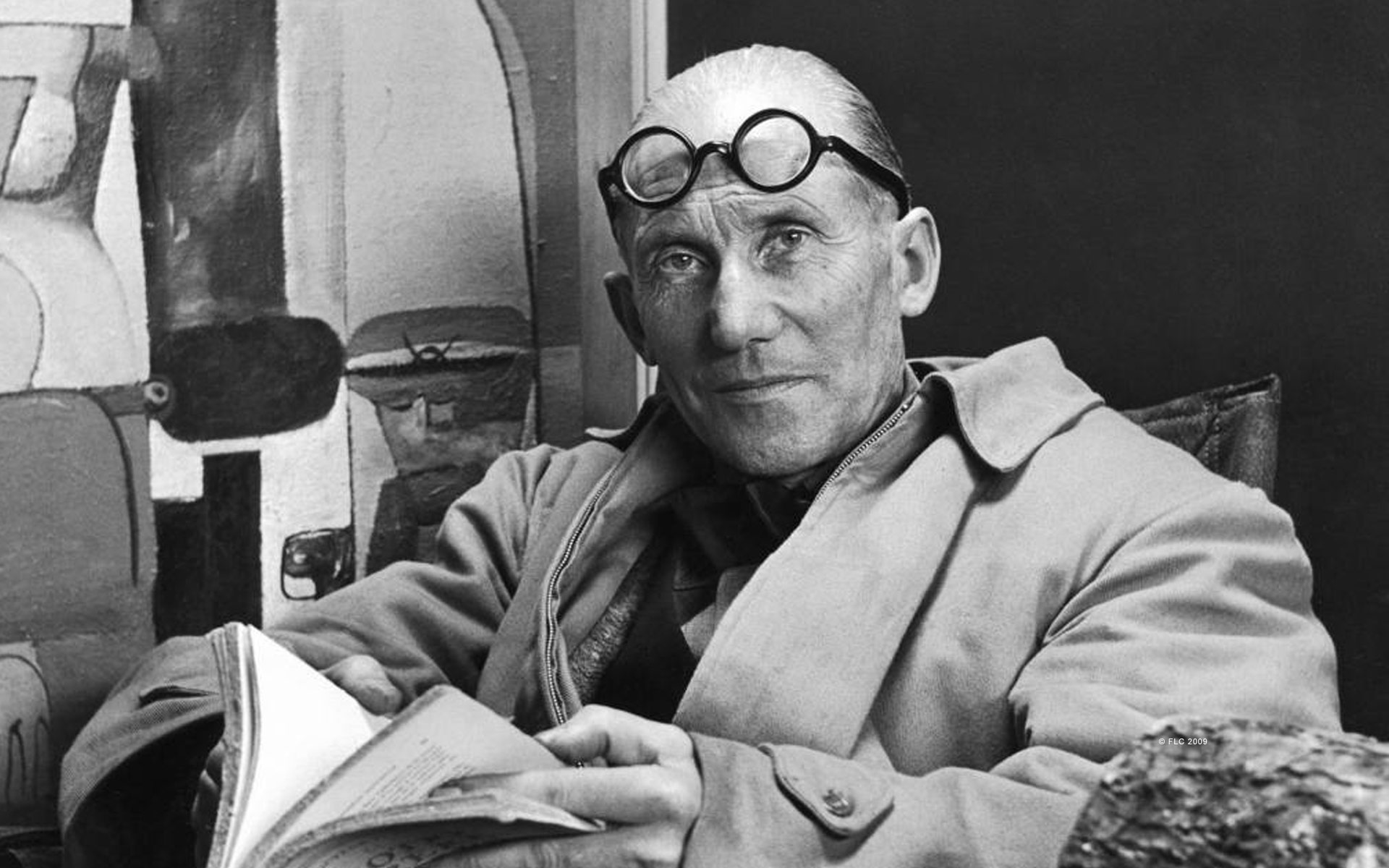

The name Pier Luigi Nervi is perhaps not well known outside his native Italy. This is perhaps because he rarely worked outside of Italy (although he collaborated with Harry Seidler on several projects in Australia) and was not an architect but an engineer.

His speciality was concrete and elevated it to a fine art, weaving complex and beautiful patterns on a variety of projects before and after the Second World War. His earlier work was led by structural necessities but this did not prevent Nervi pushing the boundaries of the available technologies and creating stunning forms in concrete.

From warehouses, bridges and factories Nervi went on to build sports stadia, arenas and cathedrals, always proving that, in the right hands, concrete can be the most beautiful and versatile material available to architects and engineers.

Millau Viaduct – Infrastructure (France )

Bridges often act as much more than a way of getting from A to B. As well as acting as a physical link they can symbolise the overcoming of ideological barriers and serve to connect ideas as well as places.

A bridge is also that rarest of structures, one that can enhance an already beautiful landscape and this is the case at Millau. A breathtakingly elegant structure and a triumph of engineering it takes the Modernist credo of "Form Follows Function" and distils it down to almost perfection.

Millau has a practical function, speeding French holiday traffic down to the Mediterranean coast and Spain, but with its English architect and French engineer it serves as a metaphor for collaboration and also shows the unparalleled ability of the human race to shape its environment and overcome huge physical obstacles.

Jack Hale and Eddy Rhead are publishers of The Modernist, a quarterly printed publication about 20th century modernist architecture and design. Check it out here.