Australia’s Housing System Needs a Big Shake-Up: Here’s How We Can Crack This

Despite two years of housing market cooling in Sydney and Melbourne, Australia stayed near the top of the global unaffordability league in 2019.

And with prices rebounding in our two largest cities, that status is likely to be reinforced in 2020. Australia’s 30-year housing affordability decline has been among the worst in the developed world.

This problem is fundamentally structural—not cyclical—in nature. Yes, periodic turbulence affects prices and rents. And yes, market conditions vary greatly from place to place.

Australia-wide, though, there is an underlying dynamic that – over the medium to long term – is driving housing affordability and rental stress in one general direction only: for the worse.

Certain key factors in Australian housing woes are, of course, far from unique.

As we argue in our new book, neoliberal policy dominance and the financialisation of housing have damaged housing system performance in many other countries as well.

Similarly, cheap debt has supercharged house prices globally, not just here. And ours is not the only comparable nation where coping with rapid population growth is part of the policy challenge.

But, as we show in our book, over the past 30 years across 18 OECD countries, our market has had the third-biggest fall in house price affordability – and the largest of any major OECD nation.

In Australia, the focus of concern is often on the challenges aspiring first-home buyers face.

Although important, this shouldn’t distract policymakers from the bigger policy problem: affordability stress affecting lower-income renters.

Being pushed into poverty by high rents is a serious issue. It affects well over a million Australians. That’s many more than the marginal first-home-buyer cohort.

Financial stress indicators in areas of high and low rents

Systemic problems have very broad impacts

Financial regulators and policymakers are starting to realise housing system under-performance doesn’t just damage the welfare of key population groups. It also raises concerns about economic productivity and systemic financial risk.

Even from a narrow “cost to government” perspective, the Australian government should treat current housing system trends as a serious budgetary concern because of impacts on future public spending.

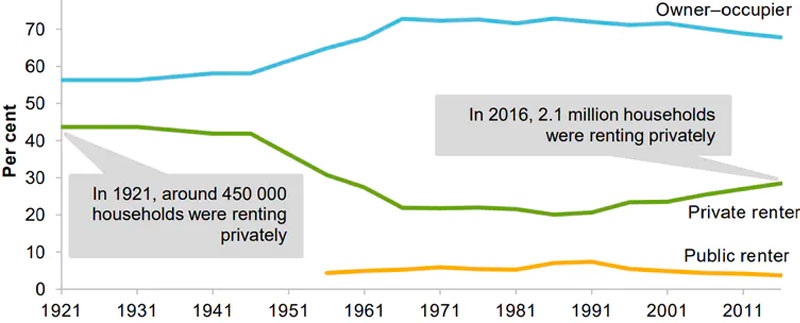

For example, declining home ownership among younger and middle age groups will filter through to older age groups over time. Increasing numbers of older, lower-income, private renters will generate political pressure to boost Rent Assistance and the Age Pension.

And pensioner numbers will be inflated if rising numbers of home owners who reach retirement age with mortgages draw on superannuation savings to pay off their debt.

Why do we need system-wide change?

A key goal must be to discourage speculation in land and housing. This would include a phased restructure of tax settings that incentivise unproductive housing over investment.

For example, most housing economists agree investor landlord tax concessions should be wound back and a broad-based land tax should gradually replace stamp duty on housing sales.

The strategy must also aim to increase diversity in the housing market.

Expanding the scale of government and non-profit housing provider activity can boost the capacity to better house disadvantaged groups.

It will also reduce vulnerability to damaging market volatility arising from the overwhelming reliance on for-profit developers building for individual buyers.

To repair the hollowing-out of housing policy-making capability within governments, the plan should include institutional reform and capacity-building.

Both levels of government should have a dedicated cabinet-level housing minister to champion the housing cause across departments.

We also need an enduring national agency like the US Department of Housing and Urban Development or the former UK Housing Corporation.

Start small and build up to far-reaching action

Our insistence on system-wide analysis and reform might seem utopian, especially given the current state of Australian politics.

There are parallels here to the challenges of climate change: many might ask how much worse things have to get before active policy action becomes irresistible as a bipartisan commitment.

In the absence of immediate system-wide action on housing, we can also point to initial reforms that Australian governments could easily adopt with minimal direct budgetary impact.

State and territory governments could, for example, follow many comparable countries in adopting planning system rules that set minimum levels of affordable housing that must be built within market housing developments.

In the realm of tenants’ rights, other states could follow Victoria in rebalancing residential tenancy laws away from their typically in-built landlord advantage. “No grounds evictions” should be outlawed.

The Commonwealth could restore the pre-1996 rules of its longstanding National Housing Agreement with the states and territories which largely ringfenced federal funding to supply and improve social housing.

All governments could commit to delivering a substantial proportion of affordable housing within residential developments on ex-government land. Many industry stakeholders advocate a 30 per cent target.

We see scope for a phased approach: first-step measures could be implemented while building the political consensus needed for more far-reaching actions.

To improve affordability and moderate the rising inequities within and between generations, Australia’s housing system must be fundamentally reformed. There is no responsible “business as usual” option.

Authors

Hal Pawson, Professor of Housing Research and Policy, and Associate Director, City Futures Research Centre, UNS.

Judith Yates, Honorary Associate Professor, School of Economics, University of Sydney.

Vivienne Milligan, Honorary Professor – Housing Policy and Practice, City Futures Research Centre, UNSW.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.