Indigenous Housing Won’t Endure Climate Change: Research

Housing in regional and remote Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities will be rendered uninhabitable by the changing climate, forcing people to leave their traditional lands, new research has found.

According to the Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute, the current state of housing in communities is not fit for purpose under current conditions, let alone under the most optimistic climate change scenarios—a 1.5 degree rise in temperature.

As part of the research, undertaken for AHURI by researchers from University of Sydney, University of Adelaide and University of Tasmania, 366 simulations, modeling three different climate zones, were conducted.

Each simulation tested the performance of standard and improved housing using different variables: temperature, humidity, ventilation, crowding, mechanical cooling and heating.

The research team modelled scenarios that included five, seven and 16 people in a three-bedroom house, a not uncommon situation in remote Australia.

University of Sydney professor Tess Lea said the findings confirmed what many had long known, that “crowding makes thermal control worse, no matter the design”.

“But even without crowding, and even with implementing current upgrade recommendations, Aboriginal housing in many regions will not be habitable with increasing temperatures from climate change,” Lea said.

“Attention must be paid to the designs, materials and maintenance regimes for sustainable housing as failure to do so risks defaulting to climate migration [not mitigation] as the de facto policy.”

Lea said during the research it became apparent that housing in its current state and stock for regional and remote Aboriginal people was unable to provide consistently healthy or comfortable indoor environments.

The negative impacts of culturally inappropriate and poor-quality housing on the health and well-being of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, especially young people, has been well-known for many decades.

Meanwhile, well-intentioned housing policies have continued to be inappropriately designed and implemented in a way to control and monitor Aboriginal communities.

The results of these policies have been dire, with overcrowding, ageing housing stock, poor quality construction and maintenance (especially waterproofing)—as well as inappropriate standardised designs that do not reflect Aboriginal cultural values and family structures—continuing to be ignored or unaddressed.

The research put forward a solution to manage the costs of providing remote housing; through a life-cycle costing (LCC) approach that considers the full costs of housing—from construction to operating to maintenance and repair costs.

“Using an LCC approach means maintenance is understood as a central consideration in the design phase and is a means of reducing significant costs later in the life cycle,” Lea said.

“The LCC analysis shows that building a house in remote Australia that can be cooled sustainably, uses fit-for-purpose building materials and appliances, and is maintained to an appropriate schedule is much more economically efficient.

“This understanding can also counter the tendency of policy makers, builders and property managers to implement ‘quick fix’ approaches without attention being paid to the economic, health and social consequences of their decision.

“It is an essential requirement for improving the long-term health and wellbeing of tenants.”

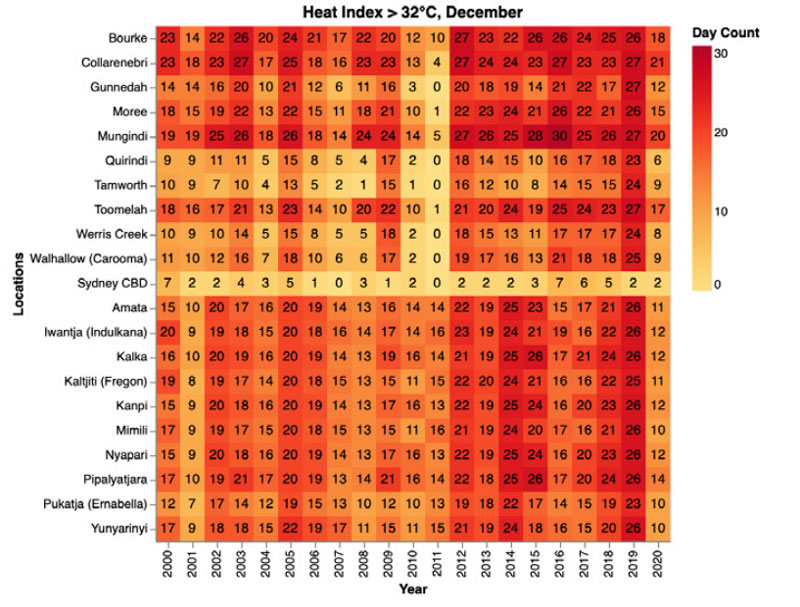

Heat index, days above 32°C, December, 2000–2020

^Source: DES, ABS and NOAA

CSIRO, along with the Australian Bureau of Meteorology, recently projected with “very high confidence” that Australia’s weather is expected to experience more frequent and hotter days, sea levels will rise, oceans will become more acidic, snow depths will decline, and extreme rainfall events will become more intense.

Australia has already experienced increases in average temperatures during the past 60 years, with more frequent hot weather, fewer cold days, shifting rainfall patterns and rising sea levels—a trend that is expected to continue into the future.

A recent study conducted by climate risk analysis company XDI— which uses vast pools of data to estimate the risks of natural hazards such as coastal inundation, riverine flooding, bushfires, soil subsidence from drought and wind damage—found that those in regional locations stand to pay the highest costs from extreme weather events.

The study covered 15 million addresses across Australia’s 544 local government areas, and is intended to be used by a wide range of parties, including local and state governments, investors and banks, to assess risks to existing and potential assets.

The study used a measure called the “total technical insurance premium”, which assigns an annualised cost of climate change-related costs for each council area.

Averaged across Australia, the report predicted the cost would be a seemingly modest 55 per cent higher in 2100 than it is today.

The number of “high risk” properties, which currently sits at 383,000, is expected to double to 735,600 in that time.