Growing Numbers Of Renters Are Trapped for Years in Homes They Can’t Afford

Low-income tenants in Australia are increasingly likely to be trapped in rental stress for years. New evidence from the Productivity Commission shows almost half of such “rent-burdened” private tenants are likely to remain stuck in this situation for at least half a decade.

Rental stress is where a low-income tenant faces housing costs that leave them without enough income for food, clothing and other essentials. The scale of the problem – commonly defined as when rent eats up more than 30% of income – is usually presented as a “point in time” or snapshot statistic.

Read more: City share-house rents eat up most of Newstart, leaving less than $100 a week to live on

As the Productivity Commission report reveals, the snapshot number in this situation has increased from 48% of low-income renters in 1995 to 54% in 2018. That’s around 1.5 million people pushed into poverty by high housing costs.

For some, of course, this will be only a temporary problem. On this basis, it is sometimes argued that concerns over Australia’s high rate of rental stress are overstated.

However, the Productivity Commission report, Vulnerable Private Renters: Evidence and Options, highlights longitudinal survey evidence showing that a low-income tenant’s experience of rental stress is increasingly likely to be long-term – not a passing problem. As the commission notes:

[…] a growing number of households find themselves stuck in rental stress.

What is the evidence for this?

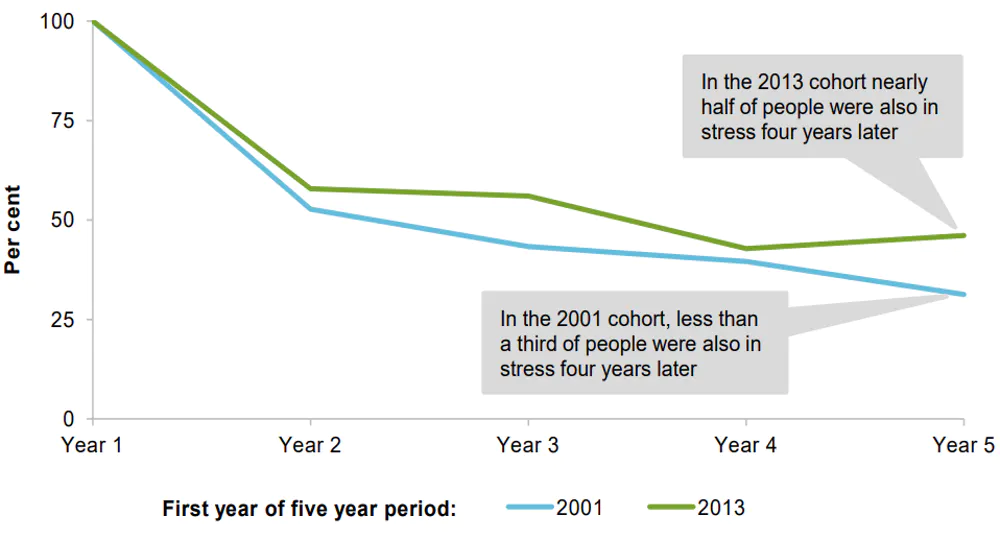

This conclusion stems from a comparison of two different tenant cohorts experiencing rental stress as revealed by survey data for 2001 and 2013. Less than a third (31%) of the 2001 cohort remained in stress five years later. But almost half (46%) of the 2013 cohort were.

So, it’s not just that more low-income earners are paying unaffordable rents at a particular point in time. This is increasingly a situation that affected private tenants cannot escape.

Beyond the obvious welfare impacts, recent work argues that excessive rent burdens may also damage human capital and, as a result, reduce economic productivity.

The commission’s findings seem to suggest the ongoing restructuring of Australia’s labour market and housing system is eroding socioeconomic and/or housing mobility. The report notes the significant fall in the numbers who manage to move from renting to owning – from 13.6% of renters in the period 2001-04 to 10.0% from 2013-16.

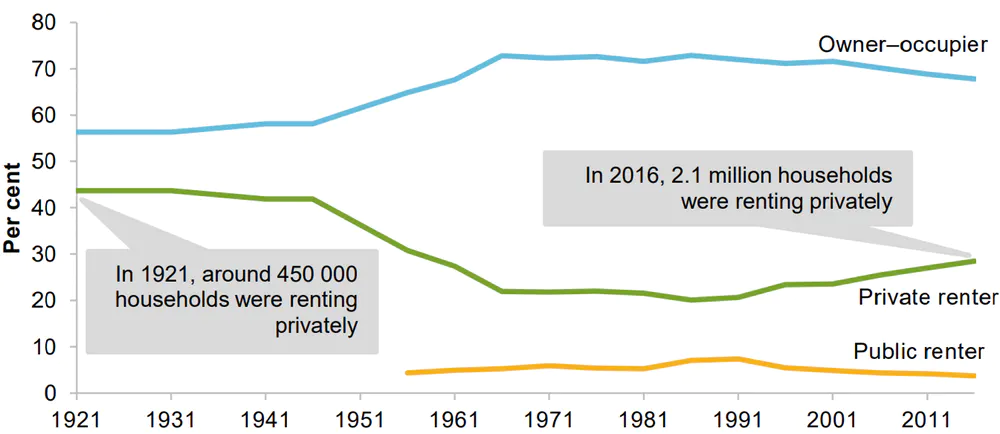

Perhaps slightly more surprising is the commission’s explanation for the rising rate of (point in time) rental stress for all low-income tenants. According to the report, this results not from increasing unaffordability for the private renter cohort specifically, but from the growing dominance of private rental housing as the tenure in which low-income households live.

Read more: Private renters are doing it tough in outer suburbs of Sydney and Melbourne

This, of course, results from the post-1990s failure of Australian governments to expand the supply of social housing to match population growth. By 2018, well over two-thirds (71%) of low-income tenants were renting in the (relatively expensive) private market – rather than from a (rent-limiting) social landlord. Back in 1996, barely half (52%) of them were renting privately.

What does this mean for policy?

The report presents some useful discussion of possible policy directions.

For example, while dismissing rent control as liable to advantage existing tenants at the expense of potential tenants, the report is implicitly critical of residential tenancy laws in most states and territories.

The report advances the broad case that tenancy law reforms, “if well designed”, can enhance tenant welfare “without substantially increasing the cost of renting”. Longer notice periods are particularly favoured because these will “provid[e] vulnerable families more time to find new accommodation and prepare for the move”.

Slightly more controversially, the commission strongly hints at support for outlawing no grounds evictions. The landlord power to end a tenancy without any need to justify the move persists across most states and territories. Discussing this power the report states:

It increases the bargaining power of landlords […] and decreases that of tenants. Landlords’ incentives to carry out obligations, such as repairs and maintenance, decrease when no grounds evictions are available, since this provides them with an avenue to terminate leases in the event of a dispute.

Read more: Life as an older renter, and what it tells us about the urgent need for tenancy reform

However, having highlighted a private rental affordability problem that is both growing in scale and becoming demonstrably more entrenched, the report is timid on solutions beyond modestly improving tenancy conditions.

It argues in general terms for an increase in Commonwealth Rent Assistance but – beyond tentatively floating a 10% rise in maximum payments – advances no specific proposal.

Expanding the social housing stock as part of the broad-ranging housing strategy Australia badly needs is scorned as “an expensive option”. This is a reference to the narrowly scoped analysis in the commission’s 2017 Human Services report. It favoured market solutions to provide low-income housing – on efficiency grounds.

The “expensive option” assertion is out of line with the more broadly framed analysis of the Productivity Commission’s predecessor, the Industry Commission. The latter concluded:

Public housing and headleasing [when social housing providers sublease private rental properties] are assessed to be more cost-effective than cash payments and housing allowances.

While the Industry Commission report admittedly dates from 1993, the subsequent failure of overwhelmingly private provision for low-income renters surely presents compelling reasons to revisit the investment case for social housing.

Read more: Australia's social housing policy needs stronger leadership and an investment overhaul

Authors

Hal Pawson, Associate Director - City Futures - Urban Policy and Strategy, City Futures Research Centre, Housing Policy and Practice, UNSW

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.