Housing affordability is becoming an increasingly pressing concern through 2021, as dwelling values continue to rise and first home buyer activity has started to decline.

Through April, national dwelling values increased by 1.8 per cent, which is six times the average monthly movement in property prices for the past decade.

Adjusting the median dwelling value in Australia for this monthly uplift suggests the typical home price rose $11,240 in the space of a month.

With such rapid increases, just how much of the housing market is still attainable for buyers?

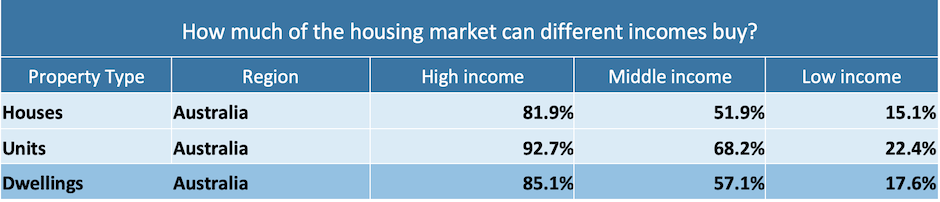

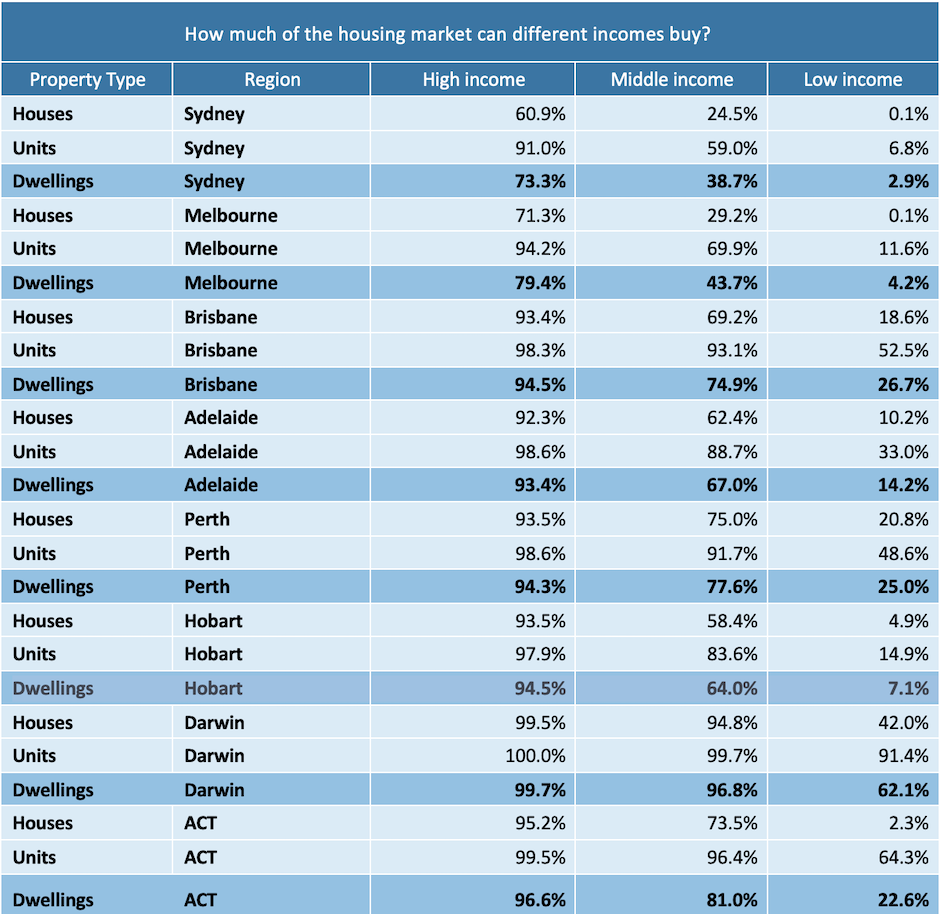

Unsurprisingly, high-income earners have the advantage in the buyer pool, with CoreLogic data suggesting high-level income earners could afford to purchase at least 85.1 per cent of Australian dwellings as of May 2021.

This includes almost 93 per cent of Australian unit stock, and 82 per cent of houses.

Middle-income households could attain 57.1 per cent of residential properties, and low-income earners could pay for up to 17.6 per cent of all Australian dwellings based on income.

To conduct this analysis, household incomes modelled by the Australian National University (ANU) Centre for Social Research and Methods were used. These included low (25th percentile) middle (50th percentile) and high (75th percentile) income estimates to September 2020, which amounted to weekly income estimates of $905, $1654 and $2,760 Australia-wide.

An estimate of borrowing capacity at these levels was made, based on a 30-year loan term with an interest rate of 2.44 per cent, and repayments based on a 30 per cent share of income.

A 20 per cent deposit was added to that borrowing capacity to determine an affordable purchase price at different income levels. These purchase prices amounted to $376,041, $685,723, and $1,144,715.

From here, CoreLogic valuation estimates were used to determine what proportion of properties fell under these purchase thresholds. No fees or additional transaction costs were factored into the analysis.