Greater Density Urged to Ease Housing Woes

Australia has to build up, not out, if it is to solve its housing shortage, according to Ray White’s chief economist.

“This really is the big solution to housing everybody,” Nerida Conisbee told about 450 delegates at Urbanity 2023, The Urban Developer’s annual three-day conference.

“If we can get more density in our middle suburbs it will allow greater inter-generational equality and younger people will be able to more easily move into suburbs they are currently priced out of.”

Conisbee, who last month was appointed chair of the Construction Forecasting Council, conceded there were high densities in inner-city Sydney and Melbourne, thanks to the amount of building during the past 15 to 20 years.

“But it drops off really very quickly,” she said.

“We’re trying to solve the missing middle and a lot of that is Nimbyism [the acronym for “not in my back yard]—people just don’t like high densities.

“A lot of it is planning ... planning can be quite tricky.

“If you go somewhere like NSW, trying to understand the variances of planning from one very small council to another very small council can be difficult.”

Conisbee’s data shows higher density would also allow for older people to downsize, although it also says the ageing population wants, but can’t always find, a suitable new home in the suburb with which they are familiar.

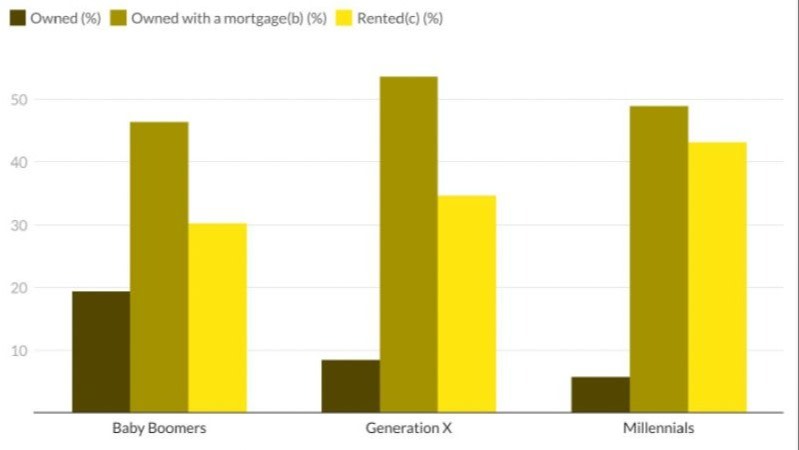

House tenure for people 25 to 39 years in 1991, 2006, 2021

She calls it “ageing in place”.

“They want to stay in the suburbs where their doctor is, their friends are, where they’re familiar, the local shopping centres,” she said after the presentation. “But they don’t want to downsize to a tiny two-bedroom apartment necessarily.

“So that transition from going to a five-bedroom home to a two-bedroom apartment is often too much.”

With Melbourne projected to reach eight million people by 2050, there are challenges in planning to accommodate growth in a way that limits urban sprawl but retains the city’s liveability.

In an address to the Property Council of Australia in Melbourne in April, the new planning minister Sonya Kilkenny pledged to promote development in established neighbourhoods rather than greenfield areas on the outskirts of the capital.

She said only 56 per cent of new homes built since 2014 were in established areas. The government’s target is for 70 per cent, with the other 30 per cent within greenfield sites.

“Application of the 70-30 requires one million new dwellings to be delivered in established areas by 2050 to accommodate Melbourne’s projected population growth,” Kilkenny said at the time.

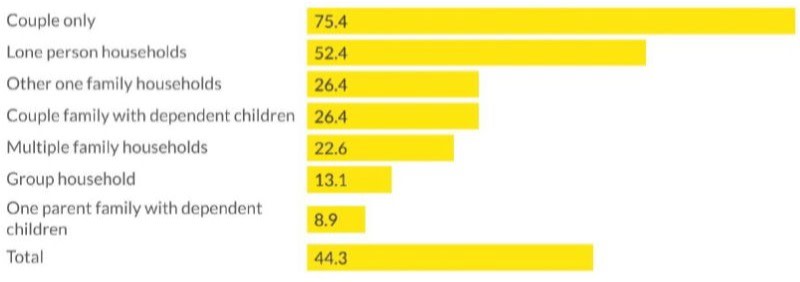

Proportion of households with 2 or more spare bedrooms

“We’re not tracking well.”

Conisbee said while housing shortages were a big problem, housing efficiency is an equally big issue, with about 13 million spare bedrooms around Australia.

She said the Australian Bureau of Statistics had calculated the figure based on the number of people per household and the relationship between those people.

The challenge was particularly acute with couples-only households.

“Three-quarters of couples-only households have two or more spare bedrooms, a third have three or more spare bedrooms,” she said.

“It’s not easy to rent those bedrooms out. People like to live on their own, they like to have a lot of space around them.”