NY Architect Oana Stanescu on Richard Meier, Kanye West and the World's First Floating Pool

Oana Stanescu experienced first-hand the fall of communism in Romania and, much later, a global financial crisis in New York City.

In between those life-changing experiences, she’s lived as a nomadic architect, developing a portfolio of work which spans nearly every continent.

In Stanescu's travels, she has worked alongside some of the world’s most celebrated people, from Pritzker Prize laureates in Europe and Asia, to award-winning documentarians in Africa and fashion icons and popstars in America.

Since settling in New York City in 2012, Stanescu has founded two architecture practices: Family — the firm behind the Hudson River + POOL featured below — and her newly-established solo venture, under her own name.

It is difficult to put a label on Stanescu, whose diverse portfolio encompasses public housing, commercial design and most things in-between, including architectural research and lecturing at Harvard GSD.

Rather than trying to define what she does, instead I got her thoughts on a few career-altering events, including founding a firm in the thick of a global financial meltdown and how her time in Africa has shaped her design philosophy.

The Women of Architecture

At the time I was interviewing Stanescu, leading architect Richard Meier had announced he was taking leave from his firm after five women had come forward with claims of sexual harassment.

I asked Stanescu about the unique challenges she’s faced as a successful woman in a male-dominated industry. She began by explaining the culture shock she experienced coming from Romania, a country with a surprising lack of gender inequality, to the United States, where she notes that most architects are white men.

Stanescu originated from a society which, while deeply misogynistic, didn't inherently draw a line between the genders when it came to the workforce. She credits that, and being surrounded by strong, powerful, working women, as the reasons she didn't grow up believing in any disparity.

"It always took me by surprise to see how more often than not genders had fairly specific and different roles in developed countries — the concept of a housewife simply did not exist in the communist world. And it is actually shocking if you pay attention to the details."

According to Stanescu approximately 80 per cent of architects in the US are men. On top of that if you add in contractors and consultants, the percentage a woman architect would professionally interact with men on a daily basis would be in the high '90s.

"These numbers would be hilarious if they weren't so true.”

Stanescu has remained steadfast in the face of this adversity, refusing to let men’s preconceived notions stop her from carrying on her life’s work. Instead, she puts the onus on them to see the error in their ways.

“Once I had to confront this prejudice — which happens on a regular basis in architecture, construction and design — I realised pretty quickly that it is not my problem, but others. Meaning, yes, of course it affects me, but it has to do with someone's deep seated insecurity and culturally inoculated false truths.

And that is an important realisation, because it is not inherently about you, as a woman or as an individual, but it's about someone being confronted with their own limitations, prejudices, with themselves. And then begins the process of them wrapping their head around it."

Stanescu recounts how on innumerable occasions, with contractors, architects, bosses, academics, project managers and clients she'd face such prejudice.

"I go on site and the contractor is looking past me, asking where the architect is. I tell him that I am, he rolls his eyes. It takes about a couple of interactions where he talks down to me, tries to trick me or god knows what else, before he learns that he does have to listen to me and that more often than not I am right and he has things to learn from me too and also, that it is in his interest to work with me rather than against me...

"But it is key that you don't let it get to you, or else you start believing this bullshit.”

She also spoke about her hopes for a more equitable future for the profession, an outlook which has been bolstered recently as the #MeToo movement has begun showing signs of impacting the design and construction industry.

“I was thrilled to see the recent article on Richard Meier — albeit six months later than other industries — because it was time the industry started having a good, deep look in the mirror and facing its darkest secrets...

It's the only way we can evolve as practitioners and as human beings. This moment in time is super important because we are talking about things that were unthinkable a year ago. It is definitely not a light or smooth or perfect process, but change never comes easy."

Stanescu sees the importance of this conversation to young boys and girls growing up today, who by her admission are now growing up "not buying any of the bullshit".

"That is amazing and that alone makes it all worthwhile.”

The Life of a Nomadic Architect

Oana Stanescu’s journey began in Resita, an industrial town in Romania which, at the time, was experiencing a political revolution against its leader, Nicolae Ceausescu. Stanescu recounts Romania during this period as a country with a tough way of making a living. “You didn’t have the luxury of dreaming, you had to do, build, fabricate your own dreams” she recalled.

Undeterred by these turbulent times, she began pursuing a career in architecture, enrolling in a six-year degree program and earning a scholarship to study abroad.

Stanescu received a scholarship to study in Milan. It was a double scholarship for two master degrees, entirely paid for.

Unfortunately, just before she was set to begin her studies in Italy, Stanescu faced a major setback which would have a lasting impact on her career, forcing her to trade in a dream of studying in Milan for one of studying in Spain.

“I had learned Italian, I had my suitcases pretty much packed, just to be told about a week before I was supposed to leave that I couldn’t go due to visa issues...

Usually, it’s something I don’t talk about because it happened so long ago but the more I think about it, the more I talk about it, because failures are as important as successes in many ways — certainly more formative than successes."

Although she lost that particular battle it did set in motion a certain set of events, which without she wouldn’t be where she is today.

Her education would eventually take her around the globe, working for many highly-regarded firms including Herzog & de Meuron in Switzerland, Sanaa in Japan and both REX and OMA in New York. By her own admission, Stanescu never thought architecture would afford her these opportunities.

“I got lucky! When I chose architecture, I didn’t know this would ever be an option but I’m so insanely grateful for the experience, for the ability to work on four different continents. It’s a really amazing thing and I would have never dreamt it would be possible. I took my first flight when I was 23…”

Architecture for the People

After working for several big-name firms in the developed world, Stanescu landed a once in a lifetime opportunity that would see her travel Africa.

As impressive as her resume may be — she emphasises that it was this “second education” that has driven her architectural philosophy, which is focused on putting people and their communities at the forefront of design.

“Everyone should go once a year to Africa, just for a bit of a reality check. It would be a very healthy thing to do.”

Although she first went to South Africa with Architecture for Humanity (AFH), as part of a team tasked with building 20 community centres in 15 different countries, it was a research project with renowned photojournalist Iwan Baan that would keep her there. Together, the pair traversed the continent, finding interesting communities and buildings worth documenting. They’d photograph these projects whilst conducting interviews with the architects behind them.

“That was a very insightful exercise, too, because I was sitting on the other side of the table as a writer, as an interviewer, talking directly to these architects. So, it has shaped my way of thinking through a different perspective. The work that we were doing was in townships, it was always in hard hit places, it was never in the cosmeticised, European mall centres.”

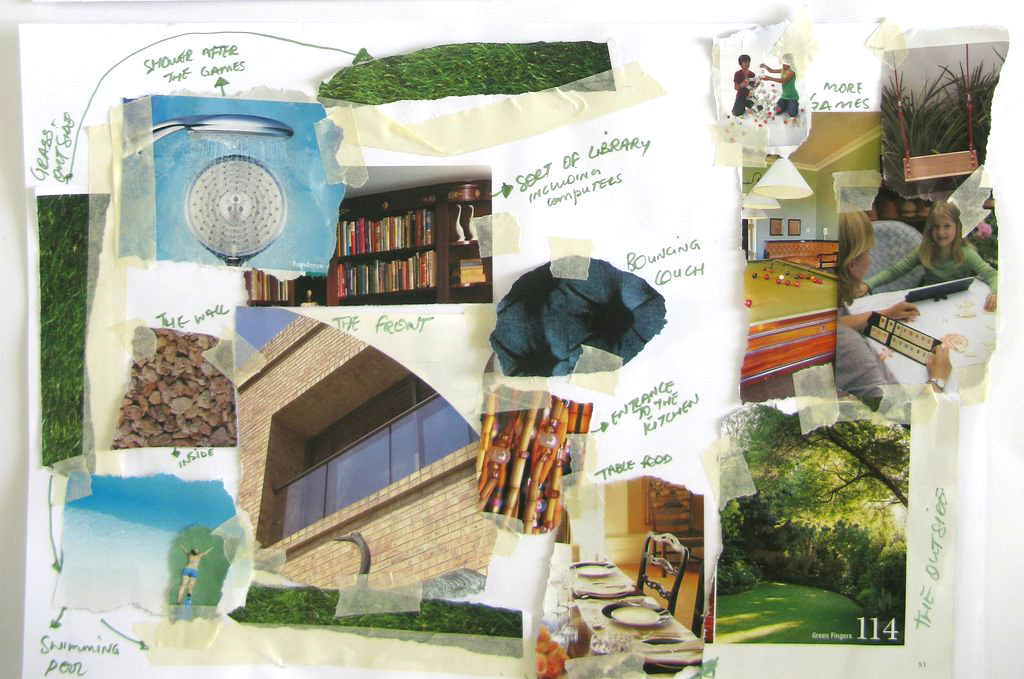

Of all the research she conducted in Africa, there were two particular memories that have remained with her very prominently to this day. The first was during the design of a community centre for high school kids in Khayelitsha, one of the largest townships in Cape Town.

“We did a workshop with [the students] to try to understand what they’d want to have in the building. On their collages there would be a picture of a shower which they found in a magazine and under it they’d write, ‘running water for after practice’. Or, there would be a picture of a tree, the most generic tree, and it would say, ‘shade for when there is sunshine’. These are 14-year-old kids, all they’re asking for is shade and running water... It definitely makes you think about the world differently.”

The second was during a research trip to Uganda. Stanescu and Baan were visiting a high school in Rakai when she was confronted with a heart-breaking reality, an entire generation of people was missing due to the disease’s outbreak.

“There were 12- to 14-year-old kids taking care of their younger siblings. And grandparents over, let’s say, 40 or something like that. But the generations in between, the generation of the parents for these kids were completely missing. You had almost no 20-year olds, 30-year olds. It was really insane to see these kids just taking care of each other.

The boy that would show us around, he was 14, super smart, amazing sense of humour. And all I could think was that his chances for a better life were thwarted because he was supposed to go to high school and the closest one was far away, but what it really shows you is that life is a lottery, we have no merit on where we're born, the conditions or the context, and some of us are luckier than others, we just tend to be oblivious to it.”

Stanescu recounts that at this time it was very easy for her to brush off the small things as she developed a much more appreciative attitude towards life.

“I remember in that context; I would always remind myself I just can’t complain about anything material. It’s just not possible because you see all these people that have so little but are able to live their lives, to sing, to dance, to keep on going with a really amazing, super inspiring spirit.”

It’s easy to connect the dots to see how this experience has shaped Stanescu’s community-driven approach to design. Especially originating from a country that, by her own admission, didn’t really value architecture much beyond its functional purpose. It was these experiences that would prepare her for an upcoming global financial crisis, by gifting her a much needed perspective.

Architecture by the People

According to Stanescu, the financial crisis was particularly unkind to architects, with some of the biggest firms, behind some of the world’s most “egocentric” megaprojects, laying off up to 75 percent of their staffs.

“I had a lot of friends, super talented people, that could have, a year prior, found a job anywhere, who couldn’t find any work overnight. Construction and architecture are probably the first industries to be hit in a very direct manner because projects stop overnight, and through that your entire office can easily disappear… But I think it also made us understand how wasteful, in many ways, the period before the crisis was and how we were part of that waste.”

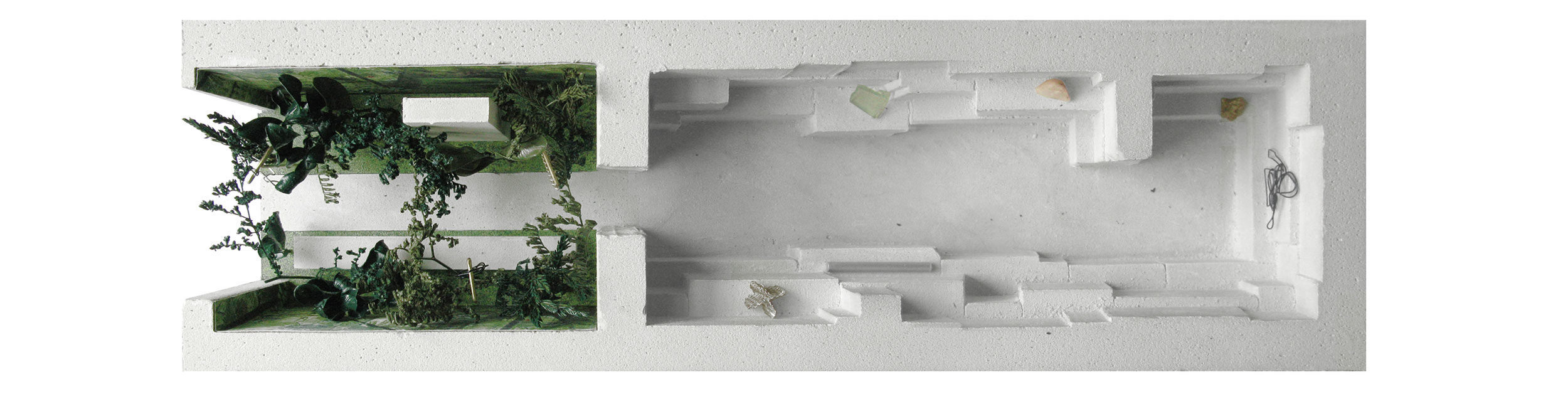

The experience made Stanescu and Dong-Ping Wong, her former-business partner and co-founder of Family, search for a deeper purpose in their architectural solutions, along with a greater sense of social responsibility. This is best embodied in their innovative proposal for the Hudson River +POOL.

Rather than following the traditional development model, which calls for securing financing, a site and a development team prior to beginning design work, Stanescu and Wong utilised crowdfunding, more specifically Kickstarter, to generate a community-developed project.

“We started with a design, the question was can you start with a design that then catalyses people and ultimately a budget, as opposed to starting with the money?

"To put it bluntly, we always say, ‘If we were to wait for someone to approach us to do the world's first floating pool, it would have been a long wait,’ right? So, how do we avoid… that issue of waiting, for the ideas to come from the people who have the actual cash?”

Stanescu and Wong hope that by the time the pool is constructed, it will have affected public policies and inspired others to start similar initiatives, putting relevant, smart and good design first in the development process.

They are aware that this model has limitations, yet they believe it’s great for raising awareness and support for a project while getting the community involved in the early stages of its conception.

“I think these crowd funded projects, or these public projects, also shed a light on the fact that people should have a say when it comes to the city. And we should look at the city as ways of, you know, ‘What can we do better? How can we improve them? How can we preserve the good things? How can we make sure public space is doing what it’s supposed to be doing?’”

The non-profit organisation set up to oversee the +POOL initiative has also recently launched a program offering free swimming lessons to children in NYC public housing. This is yet another example of Stanescu’s humanitarian background pulsing through her work.

Public Space within Private Architecture

Family continued this humanist approach to architecture in their private sector work, creating a series of highly innovative spaces that aim to breathe new life into commercial design.

“I can wholeheartedly tell you, in the most honest of ways, that I generally don’t care much about retail as a concept, as an idea. I shop like everyone else, I guess, but from an architecture point of view, the retail in itself is not that interesting to me. I’m saying that because I think that’s the key behind how we worked on these retail stores, and retail galleries and achieved something much different.”

Their most well-known retail space was for a concept store, located in Hong Kong, for Virgil Abloh’s new clothing brand, Off-White. Rather than competing with the neighbouring window displays, among them industry giants such as Comme des Garçons and Louis Vuitton, Family turned their attention to improving customer experience inside the store.

“We wanted to create something that offers something more… How do you create a place for a community? How do you allow for people to just hang out and feel good there? If they’re going to buy something, good but if not, that’s also fine. At the same time, how do you allow the people who own it to have different types of events or engagements happening in the place, where, again, it’s not all about product, product, product?”

Family achieved this by freeing up a third of the retail space, shifting the customer’s focus from purchasing merchandise to relaxing in a gorgeous interior garden. Stanescu believes these hybrid public-retail spaces will be critical to the longevity of brick and mortar stores, especially in a market dominated by online retailers.

“Convenience wise, you can’t really compete with the likes of [Amazon]… People need a reason to go to a store. And it’s never going to be just the product again. It has to be something that’s more than that. Whether it’s about community, whether it’s about the sense of place, whether it’s about a unique experience of sorts.”

Following his success with Off-White, Abloh was recently appointed as the first ever African-American artistic director at Louis Vuitton. As he takes up residency as director of men's wear at the fashion giant, it will be interesting to follow how the strategies behind Off-White stores influence the luxury brands retail experience.

The Music of Architecture

One of the recurring themes that came up throughout our interview was Stanescu’s love for music. Over the course of her travels, she has developed a close working relationship with Grammy Award-winning rapper Kanye West.

In 2014, the pair collaborated on the design of a performance stage, featuring a 15-metre model volcano, for the rapper’s 38-city tour. In fact, Stanescu was one of the lucky few whom West allowed to sit in on the recording of Yeezus, his critically-acclaimed album.

“To see how [the album] evolved over six months, to see how a song evolves from one day to another to another to another, the process didn’t seem that different to me than design, or the way that I think about design.

"In essence, you start with the first draft of a project. If it’s a model you’re going to make, it’s going to be ugly as hell. And it’s fine, but you have to start somewhere. And then you listen to it, look at it, then you do it again, then you do it again, then you do it again."

By her own admission Stanescu still gets “very geeky and excited” when she comes across those moments where she discovers something different, new or unique.

For her, the design process is very much about discovery and that’s where she sees the overlap between architecture, art and music.

“Design is a discovery process. When you start a project, you don’t know what you’re going to do, you’re not supposed to know. If you know from day one exactly what the project is going to be then, chances are, you’re just going to repeat something that either has been done, or you have done before.”