Resources

Newsletter

Stay up to date and with the latest news, projects, deals and features.

Subscribe

There was no surprise in the board of the Reserve Bank of Australia lifting interest rates at its July meeting. The only question was by how much.

Would it be a “regular” increase of 25 basis points? Or a double-whammy of 50. The markets tipped the double and were proved right.

The central bank lifted its cash rate target from 0.85 per cent to 1.35 per cent—taking Australia’s official interest rate to its highest level since July, 2019.

This is sign of how seriously governor Philip Lowe and his fellow board members regard the threat of domestic inflationary pressures and a hot labour market to economic stability. Expect more action to follow.

The primary reason the decision is the surge in inflation across the Australian economy.

In part rising prices have been driven by events overseas—principally Russia’s war on Ukraine pushing up oil and food prices.

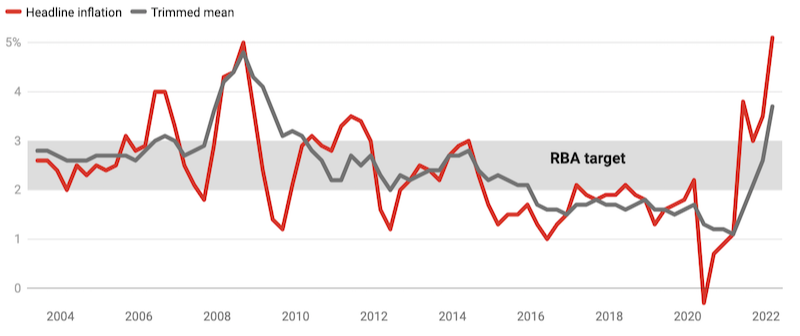

But it’s not just a supply issue. Rising demand for goods and services in Australia are contributing just as much to the bank’s expectation that inflation, having surpassed 5 per cent in the March quarter, will reach 7 per cent by the end of 2022.

Consumer price inflation

Evidence of this can be seen in the Australian Bureau of Statistics’ latest report on inflation. It shows that, even excluding food and fuel, prices across the economy rose by 4 per cent over the past year.

My own analysis of these numbers suggests most of the current inflation surge is being driven by higher demand. This is something best solved by tighter monetary policy (to restrict spending) and thus higher interest rates.

On top of rising prices, Australia’s labour market is also running piping hot. The unemployment rate of 3.9% is the lowest level in 40 years.

The number of businesses looking to hire new workers is at an all-time high, with 27 per cent having difficulties filling positions, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics.

This strong demand for labour is putting upwards pressure on wages, which will keep inflation high if not offset with higher interest rates.

A big challenge the Reserve Bank of Australia faces when setting interest rates is that inflation data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics is only published every three months.

Overseas counterparts have the benefit of monthly inflation data. But at its July meeting the RBA board had to rely on inflation data published in late April. The RBA is flying somewhat blind until the next inflation report in June. What that report shows will be a key factor as to how high interest rates will rise over the rest of the year.

Last month the financial markets expected the cash rate would eventually peak at about 4 per cent in 2023. They’ve since reduced this forecast to a high of 3.3 per cent.

Still, this would push the average interest rate that home buyers are paying on their mortgage to more than 5 per cent.

The market predictions imply the RBA board will, over the five monthly meetings it has left in 2022, increase interest rates by an average 0.33 percentage points each time.

Some doubt rates will rise that high that fast. But over the past year the markets have been much better at forecasting interest rates than economists and the Reserve Bank’s own guidance. We should ignore these market signals at our peril.

So, expect—and plan for—interest rates to increase every month for the rest of the year.

Isaac Gross

Lecturer in Economics, Monash University