Rethinking Contemporary Architecture in Tehran

Early last year, economic sanctions against Iran were lifted after years of economic isolation.

The lifting of the sanctions, which had crippled the Iranian economy, allowed Iran to once again become an active member of the international community – opening the economy to international trade and investment.

There is a growing demand in Iran for contemporary lifestyles and investment in tourist infrastructure, which has created new opportunities for architecture professionals in a nation once perceived as being on the margins of globalisation.

To better understand the diversity and complexity of current architecture being practiced in Iran, The Urban Developer asked RMJM Arta Tehran, the local studio based in Tehran of the international architecture and design firm RMJM, to provide an overview of contemporary architecture in Iran against a complex and ancient history.

To the question of where bold experimental architecture is being practiced, there are perhaps many more immediate responses than Tehran – from Brasilia to New York, Melbourne to Shanghai. Some notable voices in the industry have recently proclaimed the arrival of a new era of architecture and urbanism in the capital of the vibrant, yet often overlooked, nation of Iran.

The largest city in Western Asia, Tehran, is not the only city in the country where excellent boundary-breaking design is being practiced. Isfahan, Shiraz and Tabriz are now all following Tehran’s lead.

RMJM Arta Tehran seeks to unveil what makes Tehran worthy of its moment in the spotlight and the favourable context that led to a new generation of highly-educated architects no longer happy to simply follow global trends, but increasingly keen to start them.

The weight of history

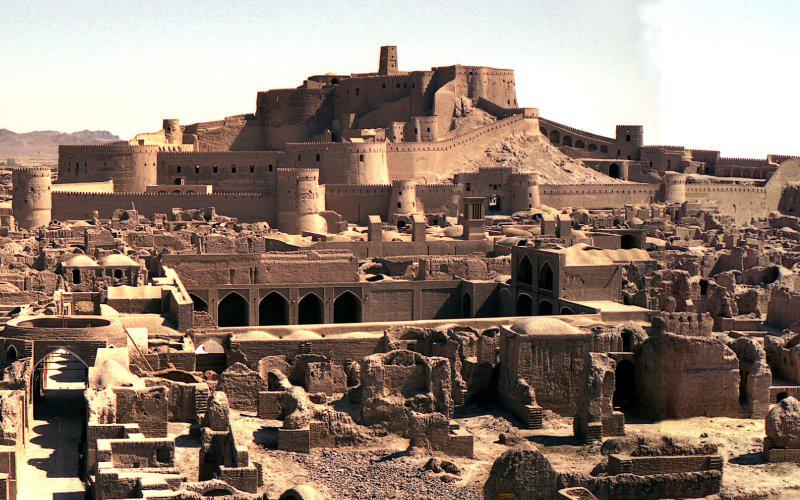

Persian identity has been shaped by centuries of progress, from Persepolis, the capital of the Persian Empire to Arg-e Bam, where the world’s largest brick structure can be found.

During the Pahlavi dynasty, which lasted from 1925 until 1979, a tendency to imitate European movements, namely Brutalist architecture, arose. After the Islamic revolution, in reaction to fears of loss of Persian identity, there was a wave of rediscovery of Islamic identity which led to its integration in modern designs, particularly in Tehran.

The Citadel of Bam is believed to have been built around 579–323 BCEMain features of contemporary Iranian architecture

Following the lifting of sanctions, growing investment – alongside a rapidly expanding economy (GDP growth in the first half of the Iranian calendar year reached 7.4%) – is fuelling the creation of new residential projects as well as hotels and infrastructure.

The country is undergoing relative stability compared to the uncertainty of the post-revolution period but the outstanding work being carried out by local architecture and design studios in the past decade can not be explained by this factor alone.

There is evidence, for instance, that there is an exceptional know-how in relation to the newest rendering software. This is essential for architects to be able to put onto paper such an ambitious vision as ones that seeks to marry traditional heritages to avant-garde inspirations in both public and private arenas.

It is this expertise that allowed for widespread renovation and a new era of construction that mitigated some of the natural growing pains of the densely populated capital.

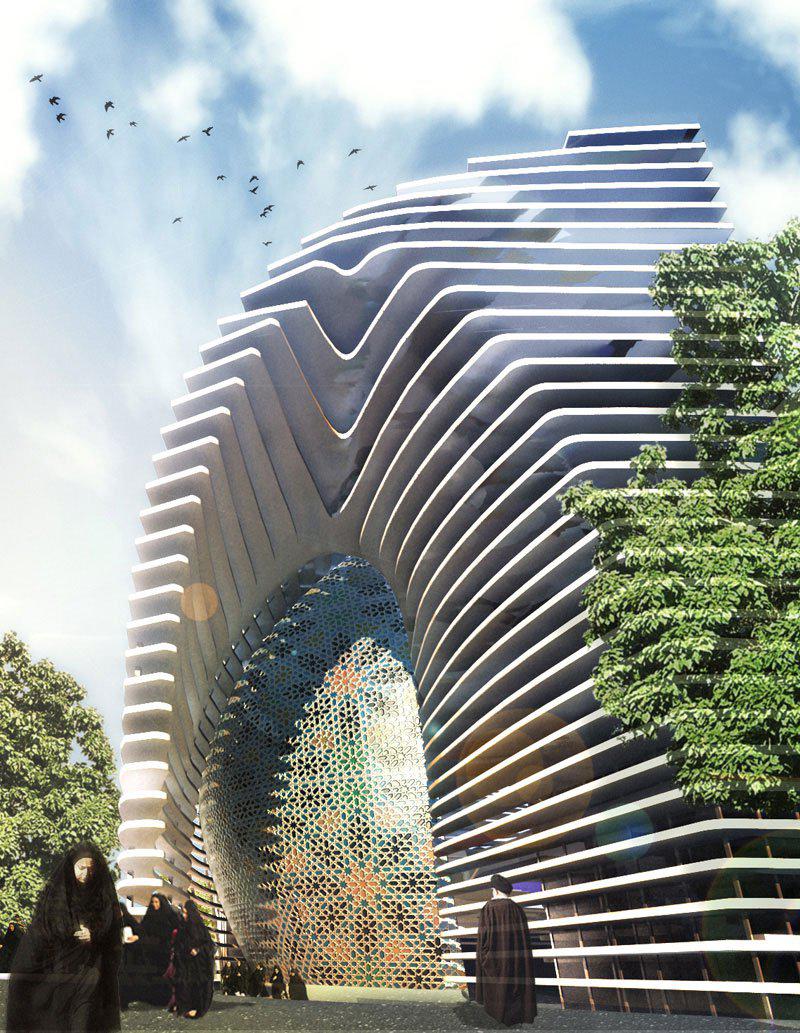

Mosque (Amir Al-Momenin) Proposal / CAAT Architecture Studio - Courtesy of CAAT Architecture Studio

What is not so often discussed in this narrative of continual improvement is the uphill battle against “build-it-fast, build-it-cheap developers” and ubiquitous kitsch as Ali Dehgani of Ayeneh Office articulated in a Dezeen article from last year.

Concerns for low-quality design and execution have been expressed by people of diverse backgrounds – not only from an erudite elite. Professor Asma Mehan, Research Fellow at Deakin University, claimed the protection of modern architectural heritage is at risk of being razed or collapsing, another significant concern.

The history of Iran does not only pertain its magnificent Persian design but also the fascinating structures built in the late 19th and 20th century, a period of Iran’s openness to the West and its architectural movements.

The inverted-Y-shaped Azadi Tower, built in 1971 to commemorate the 2500th anniversary of the first Persian empire, is one of Tehran's visual icons.

Anxieties regarding the path Iran is undertaking don’t end there. The Iranian economic daily newspaper, Financial Tribune, has recently reported on the cost of the “high-rise fever” in Tehran.

Air pollution and the disappearance of green spaces, 4,000 hectares in total to be precise, are two of the most evident negative consequences of this obsession according to the Ministry of Roads and Urban Development.

This has caused great alarm not only to environmentalists but to average citizens who pay the direct consequences of these acts on their quality of life. This has become such an urgent matter that the High Council for Urban Planning and Architecture had to ban the construction of buildings higher than 11 floors. The numerous projects which obtained permits beforehand, will carry on.

The Iran Historical Car Museum

The Iran Historical Car Museum is located approximately 20km west of Tehran. The museum houses one of the largest and most valuable car collections in the world, comprising sports cars, limousines, motorcycles and carriages owned by the last Shah of the Pahlavi Dynasty, Mohammad Reza Shah.

It is not immediately apparent why this project is emblematic of the new wave of local architecture to reinterpret the role and path to be taken by the contemporary Iranian architect. A more thorough analysis however, reveals its significance beyond its conspicuous aesthetic merits.

This project is remarkable due to the challenges it faced. The car museum aims to become a place that challenges the idea of the necessity to distinguish one architectural movement from the movement that precedes it – an ode to the idea of continuity.

The linear corridors designed along the display paths function as transitional spaces that embody this sense of exchange between the past and the present.

In this sense, the museum becomes a place where visitors can experience the passing of the time and witness an explicit dialogue amongst different traditions.

The client appointed RMJM to transform the existing warehouses into a museum and define a new character for the existing complex in which visitors could experience a vivid recreational and historical atmosphere

The project gave a new character to the building that counterposes the maximalist kitsch that prevails in many areas of the city. The existing complex will allow visitors to not only experience a vivid recreational and historical atmosphere but also witness the very best of contemporary local architecture.