Sydney, Melbourne Workers Still Slow Returning to Office

Workers in Australia’s two biggest cities have been stubbornly slow to return to the office, according to figures released by the Property Council of Australia on Thursday.

Office occupancies in Sydney and Melbourne rose by just 1 per cent in each city in August, with the Victorian capital at just 39 per cent of pre-pandemic levels. Sydney occupancies fared better, rising from 52 per cent to 53 per cent.

Perth was the only city to witness a slight drop in occupancy from 71 to 69 per cent, according to the council’s figures for August.

Adelaide had the biggest rise, with occupancy climbing from 64 to 71 per cent, while Brisbane increased from 53 to 57 per cent. Canberra went from 61 to 64 per cent.

The occupancy figures—which are an average of each day—were gleaned from a survey in the field between August 25 and August 31.

The commercial property lobby group remains upbeat about the results with chief executive Ken Morrison saying that despite the small increases in occupancy “the data reveals a resilient office market, with peak days remaining high across most of the nation”.

“While the results are still a way off the previous recovery high points seen around May in 2021, they show the resilience of CBD office markets, with occupancy levels remaining stable throughout a challenging period,” Morrison said.

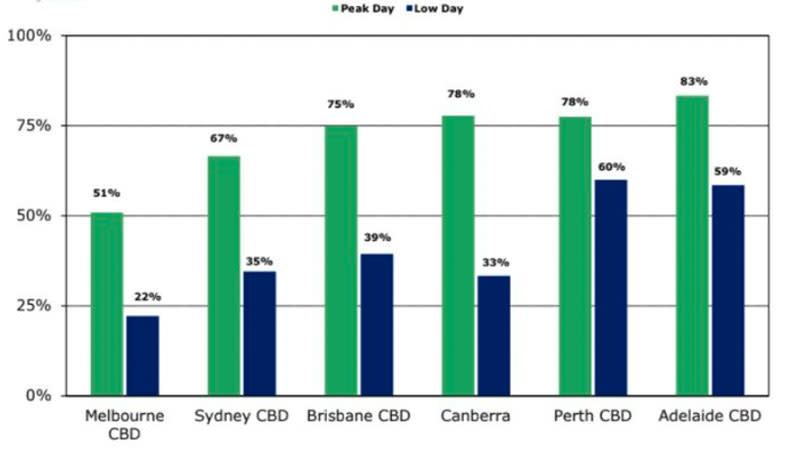

What is the peak and low day level of occupancy in office buildings?

Global commercial real estate services firm Cushman and Wakefield says the survey findings are consistent with what they are seeing in Sydney.

“There has definitely been an upward trend in occupancy levels across the CBD particularly on Tuesdays, Wednesdays, and Thursdays,” associate director of office leasing Andy Cox said.

“Whilst the increase we’ve seen in August isn’t substantial, this is in part due to the ongoing industrial action disrupting public transport in addition to the protracted flu season,” Cox said.

“We are seeing more businesses implement a return-to-office strategy with greater confidence including Goldman Sachs, Apple and Google, and anticipate this will further accelerate these numbers.”

The property council’s Morrison acknowledged Melbourne occupancy “remained a concern” but hoped that would start to lift again as the latest wave of Covid infections receded and weather became warmer.

However, in a study released late last month RMIT researchers found workers in Melbourne’s CBD spent only about 17 hours each week in the city.

The study—the first of its kind in Australia—surveyed more than 2000 Victorians living in Melbourne, its suburbs, and regional centres.

One of the report’s authors, Dr Alexia Maddox, said Melbourne’s long lockdown had led to workers rapidly adopting technology in order to be able to work remotely.

“The city is full of services, full of people of different occupational styles, but it’s the knowledge workers—which are the higher paid jobs, the managerial and executive positions—they were the ones with the greater ability for that kind of work,” Maddox said.

“Cities still hold an important place, so this became a big question for us. And it looks like this work from home trend is going to really force that decentralisation of the workforce,” she said. “And while not everyone will be able to do it, it is going to shift services away from the city.”

Maddox said people needed to think about what role they wanted from a city.

“How does a central built environment service a decentralised workforce and provide digital infrastructures that keep us engaging with that kind of core social, political, and capital infrastructure that the city really does bring together,” she said.

Despite the impacts of the pandemic and a stalling in occupancy, the property council’s office market report, which tracks leased space, showed companies leased more space in the country’s cities over the first six months of this year, with demand growing by 0.5 per cent.