Will The Automotive Industry Shake Things Up For The Future?

By Clay Carter

The global automotive industry is at an inflection point; one that is probably as important as the transition to mass production pioneered by Ford Motor Company in the early twentieth century.

Let’s face it, after 110 years the automotive industry is ripe for another disruption. Not only is the internal combustion engine under threat by regulation and alternative sources of power but driving itself may change dramatically with semi-autonomous and autonomous vehicles on the way along with ride sharing (Uber, Lyft) imperilling car ownership itself.

Within this massive paradigm shift are two attractive and investible disruptive sub themes – the electrification of the automotive fleet, and the proliferation of semi and autonomous vehicles. These two themes are attractive because it is very early in the adoption cycle, the addressable market is global and extremely large, regulation is a positive not a negative force, and the major players are numerous, well capitalised, and for the most part attractively valued.

Going electric

Global electric vehicle sales have risen quickly over the past five years, fuelled by generous purchase subsidies, falling battery costs, fuel economy regulations, growing commitments from most of the car companies, and rising interest from consumers.

In most markets though, electric vehicles still represent fewer than one per cent of total vehicles sold. Contrast that with environmentally conscious Norway where electric vehicles are now 25 per cent of sales.

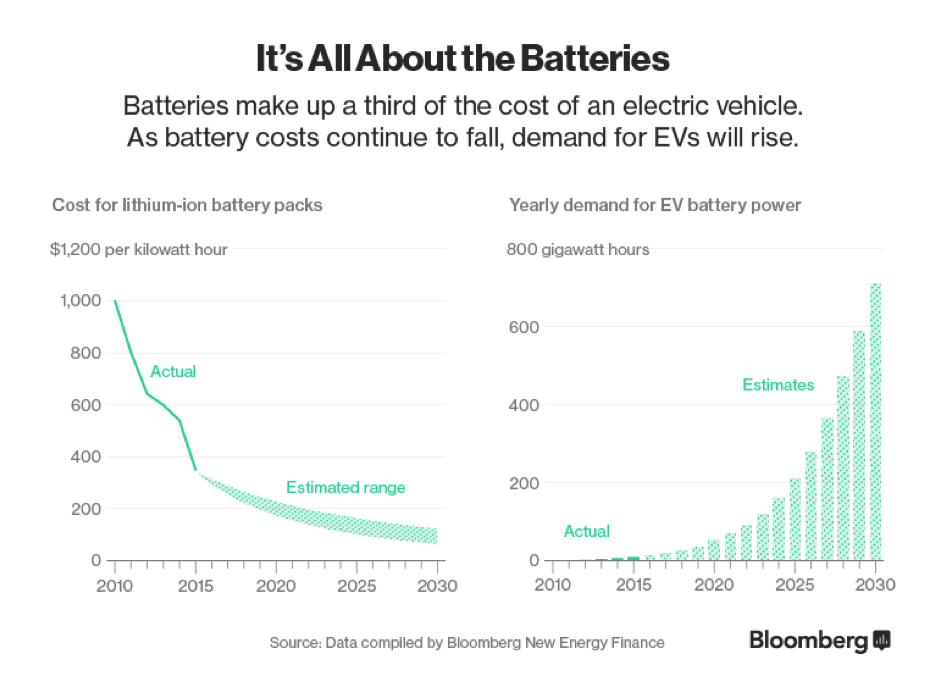

The average price of lithium-ion battery packs used in electric vehicles fell 65 per cent during the 2010 –15 period from $1,000/kWh to $350/kWh and with improvements in battery chemistry, scale, and better battery management systems, the price continues to drop.

Costs have fallen further and faster than many had expected. They are now forecast to drop below $100/kWh in the next decade, and if semi-solid electrolytes and silicon-infused anodes are implemented, along with other technological advancements, the price could possibly fall as low as $50/kWh– $60/kWh in the longer term.

Electric vehicles should become competitive with comparable internal combustion engine vehicles as early as 2020 on a total cost of ownership basis, and even earlier for high-utilisation vehicles such as delivery fleets and taxis.

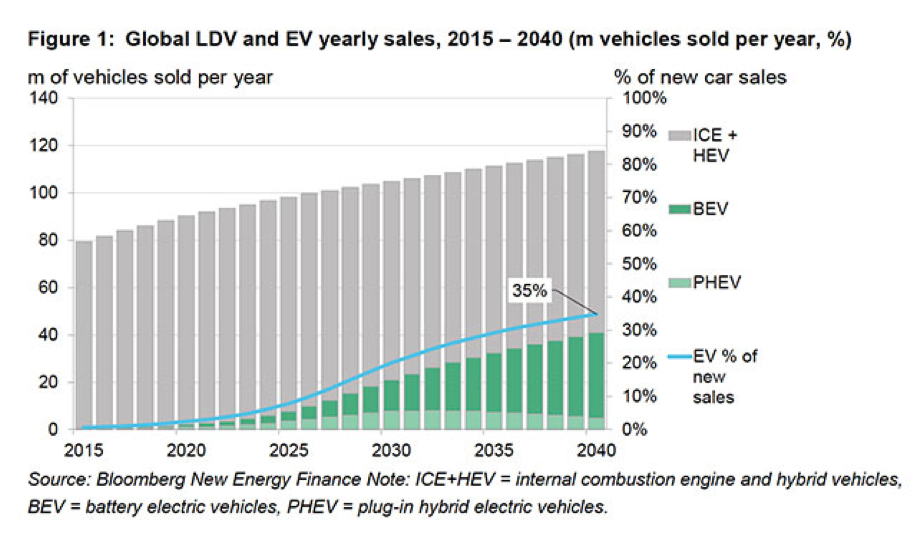

Consumer interest is rising: Tesla’s Model 3 launch in 2016 attracted over 400,000 reservations and deposits for a vehicle that will not be available until late 2017 at the earliest. By some estimates, electric vehicles will command a 35 per cent plus market share of all vehicles sold by 2040. (see figure 1)

For a change, the regulatory environment is a net positive for electric vehicle adoption as global and national fuel economy regulations are pushing both hybridization and electrification of the total vehicle fleet. The U.S, the European Union, and China in particular have set aggressive targets for automakers to meet. Certainly some of this will be achieved through improvements to internal combustion engine vehicles, but this will become increasingly difficult as standards tighten further in the 2020s.

Car companies and their suppliers are responding by dramatically increasing the number of plug-in and electrified vehicles on offer. In fact, lawmakers in the German Bundesrat have recently voted to ban vehicles powered by gas and diesel by 2030.

The non-binding resolution will place more pressure on the EU to promote zero-emission mobility, even with the long time frame in place. That in part explains the very strong electrification push recently out of European players Volkswagen, Daimler, and BMW.

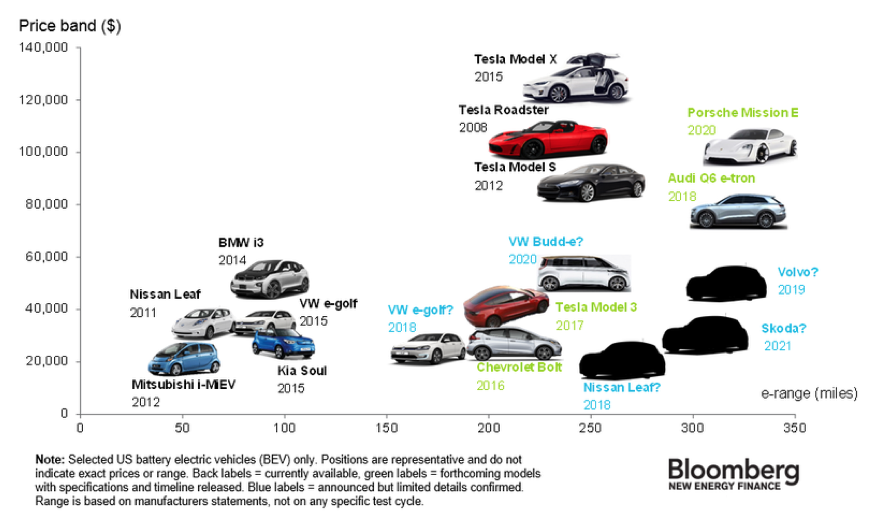

Electric vehicles still have limitations such as a lack of range and poor charging infrastructure but this is only temporary as improvements in battery technology and use of advanced materials (to reduce weight) will soon make longer trips a reality.

Tesla is building out its charging network in its major markets. Other companies will follow suit. If Tesla’s current models are any indication, electric vehicles drive as well if not better than internal combustion engine vehicles in terms of acceleration, handling and braking. As the mass market Tesla model 3 (late 2017) and the Chevrolet Bolt (late 2016) come to market, I expect adoption to accelerate. Electric vehicles are clearly here to stay.

The rise of the autonomous vehicle

The McKinsey Global Institute in its influential 2013 report entitled “Disruptive technologies: Advances that will transform life, business, and the global economy” included autonomous and semi autonomous vehicles as one of the 12 most economically disruptive technologies with an estimated economic impact of $US$200 billion to $US1.9 trillion per year by 2025 due to improved safety, time savings, productivity increases, and lower fuel consumption and emissions.

Considering over 1.2 million people are killed on the road every year and we are in a climate change crisis, self driving vehicles are clearly a “must have”.

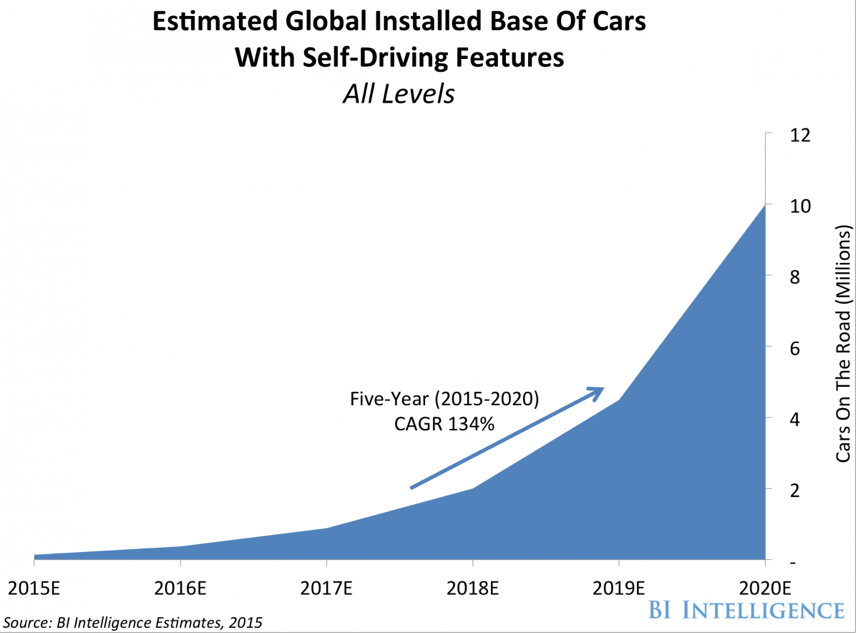

The reality is self-driving cars are not some futuristic auto technology; in fact, there are already cars with self-driving features on the road. Tesla cars have been driven coast-to-coast in the U.S. on the “auto pilot” feature for ninety-seven per cent of the driving time.

Google cars have recently surpassed two million autonomous miles on public roads.

As McKinsey points out “Technology is not likely to be the biggest hurdle in realising these benefits. In fact, after twenty years of work on advanced machine vision systems, artificial intelligence, and sensors, the technology to build autonomous vehicles is within reach as a growing number of successful experimental vehicles have demonstrated.

"What is more likely to slow adoption is establishing the necessary regulatory frameworks and winning public support.”

Tesla has announced that its customers would be able to summon a car across the country by 2018. The company is also set equip all its fleet – Model S, X, and the Model 3, with what will eventually be a fully autonomous capability – at extra cost of course, once the systems have passed rigorous safety tests and as the network “learns” from the miles driven.

The major auto original equipment manufacturers (OEM) such as BMW, Ford, General Motors, and Volkswagen are expecting to release their first self-driving cars on the market in 2020–21.

Autonomous driving capability is a computational problem and needs powerful in-car computing power capable of handling data from multiple sensors to achieve full surround vision, a key component in the development of fully autonomous vehicles.

Many established companies as well as start-ups are working on imaging and sensing hardware to communication modules for wireless connectivity, mapping, and driving data storage. Some of the leading companies in this field are listed in Macrovue’s “Car of the Future” share portfolio.

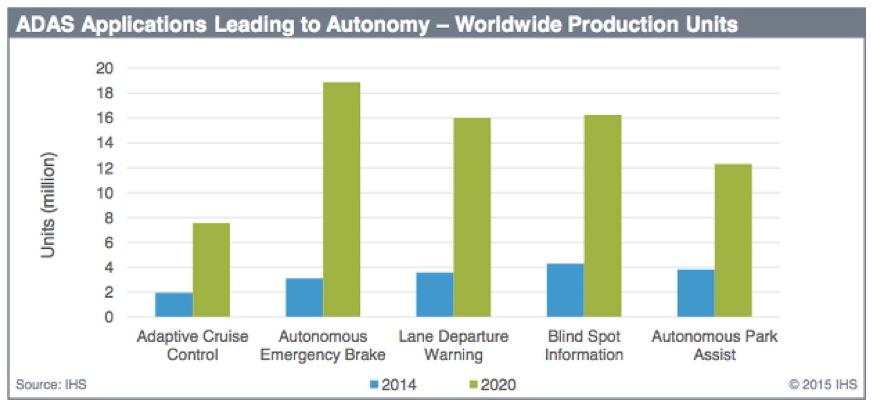

An attractive sub-theme within autonomous cars is the strong growth trajectory of Advanced Driver Assistance Systems (ADAS) which by virtue of the technology employed, is directly related to self-driving cars and is already in numerous models.

Essentially, ADAS contains the building blocks for fully autonomous driving.

ADAS technology applications for drivers include adaptive cruise control, adaptive high beam control, autonomous emergency braking, dynamic brake support, forward collision warning, headway monitoring and warning, lane departure warning, lane keeping, and construction zone assistance.

ADAS demand will be driven as much by regulators as consumers over the next decade. The EU New Car Assessment Program (NCAP) is awarding higher ratings (4 & 5 stars) to cars with automatic emergency braking. It is expected that by 2017 all cars will need ADAS to achieve a 4-star rating.

In the U.S., the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration recently announced it was adding two automatic emergency braking systems to its recommended safety features. Unofficially some ten auto OEM vehicles will add autonomous emergency braking by 2020 in the U.S.

Drive into the future - 3 top international stocks

Tesla

Tesla has a highly differentiated business model, appealing product portfolio, and leading-edge technology, which some analysts say are more than offset by above-average execution risk and valuation that seems to be pricing in a lot of good news. The company is led by Elon Musk and is probably the most controversial name in the group.

Tesla does its own stamping, body welding and high pressure aluminium die casting, and even its own seats and to a large extent its own autopilot system.

Mobileye

Mobileye NV is a developer of leading edge automated driver assistance technologies (ADAS) and one of the few “pure plays” on self-driving vehicles. Its monocular vision platform helps drivers improve safety, avoid accidents, and revolutionises the way individuals drive. The company's products contain proprietary software algorithms bundled on its revolutionary EyeQ system-on-a-chip (SoC) and are integrated into vehicle electronic and control systems.

Mounted at eye level these systems recognise signage, roadway features, other vehicles, and of course objects such as cyclists, pedestrians and road hazards. This “machine vision” is a necessary precursor to semi and fully autonomous vehicles.

Autoliv

Autoliv Inc. develops and manufactures automotive safety systems for automobile manufacturers. It operates through the Passive Safety Products and Active Safety Products segments. Passive Safety Products include airbags, seatbelts, steering wheels, and restrain electronics. Active Safety Products comprises camera vision, night vision, and radar systems. The company was founded in 1997 and is headquartered in Stockholm, Sweden.

More than half of Autoliv’s active safety revenue currently comes from its ADAS radar products which are used for forward collision warning, blind spot detection, adaptive cruise control, and other ADAS functions.

Clay Carter is a senior international investment specialist at online brokerage macrovue.com.au.