Zero Inflation Means the Reserve Bank Should Cut Rates as Soon as it Can, on Tuesday Week

What do US pizza executive Herman Cain, US conservative commentator Stephen Moore, US Chief Justice Earl Warren, and Australia’s Reserve Bank governor Philip Lowe have in common?

More than you might think.

The immediate issue for Lowe is Wednesday’s inflation figures released by the Bureau of Statistics. Inflation for the first quarter of 2019 came in at 0.0 per cent. Zero. Nada.

Taken together, the sum of consumer prices moved not at all between the last quarter of 2019 and the first quarter of 2019. The annual increase (all of it in the last three quarters of last year) was 1.3 per cent.

However you cut the numbers, inflation is now incredibly low. The Reserve Bank’s measures of so-called underlying inflation (that mute the effects of sharp movements in things such as the prices of fruit and vegetables) are at the same level they were in 2016 when the Reserve Bank cut rates twice – in May and then August.

The Reserve Bank must cut

It has to do it again. The market expects it and is pricing in a cut.

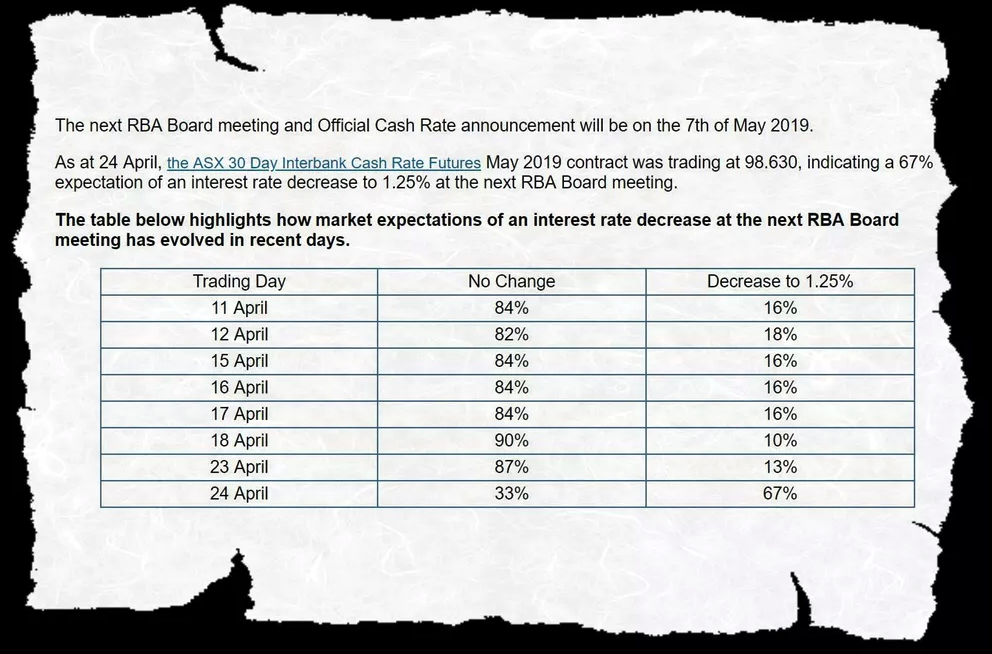

Trading on the Australian Securities Exchange implies that 67 per cent of those wagering real money expect the Reserve Bank to cut its cash rate from its present record low of 1.5 per cent to another uncharted low of 1.25 per cent when it next meets to consider rates on Tuesday May 7, a fortnight before the election.

A day earlier, before the release of Wednesday’s shockingly low inflation figure, only 13 per cent expected a cut on Tuesday week.

Three days after the Reserve Bank meeting, and just one week before the election, Lowe is due to release his quarterly report on the state of the economy and his stance on interest rates. He’ll find it easier to write if he justifies a cut.

Not only is inflation far lower than he is aiming for, but economic growth has plummeted to levels that imply annual growth of closer to 1 per cent than the present 2.3 per cent or his forecast of 3 per cent by December. Strong house price growth, that would have once been a reason for caution about cutting rates, is no longer a consideration.

A broad cross-section of market economists expect a cut on Tuesday week.

Westpac’s Bill Evans has long predicted 50 basis points of cuts this year, and on Wednesday ANZ economists Hayden Dimes and David Plank said:

The downward surprise to core inflation in the first quarter leaves the RBA with little choice but to cut the cash rate by 25 points at its May meeting, with another basis points likely to follow in August.

The Reserve Bank’s inflation target of 2-3 per cent has become a joke. Inflation has rarely even entered that range the entire time Lowe has been governor.

Lowe keeps hoping for lower unemployment to spark wages growth, but despite unemployment being consistently at or near its long term low of 5 per cent, nothing has much happened, for almost a decade.

Most observers think that unemployment would need to be much lower – closer to 4 per cent than 5 per cent – for wages to take off.

Politics makes it urgent

Then factor in the election. Labor is odds-on to win. If it does, then there is a chance of fairly radical industrial relations reform. Think about the wish list of Australian Council of Trade Unions Secretary Sally McManus. That seems unlikely to me because of Labor’s extremely sensible economic team, but it’s possible.

Whether it happens or not, until the industrial relations landscape becomes clear businesses are unlikely to do a lot of hiring. Why hire a bunch of folks if you don’t know what you might have to end up paying them or how easy it will be to let them go or change what they do?

That uncertainty is likely to put more downward pressure on wages than whatever upward pressure comes from Labor heavying the Fair Work Commission Labor into reversing its recent penalty-rates decision.

The Bank is losing credibility

All this suggests that the Reserve Bank has waited far too long for wages to tick up of their own accord.

We’ve had recent lessons from the US about the importance of credibility in central banking.

Donald Trump’s nomination of pizza executive Herman Cain to the board of the US Federal Reserve has been withdrawn after sexual harassment allegations, his nomination of Stephen Moore is in doubt after a series of derogatory public remarks he made about women.

They have political problems. Their nominations are in trouble because they are, to put it bluntly, grossly unqualified to govern the Federal Reserve.

The Reserve Bank’s problem is obviously different. It enjoys an impeccable reputation. But repeatedly seeming to ignore inflation numbers (and its own targets for inflation) is putting that reputation at risk.

Having resolve is important. The Reserve Bank isn’t supposed to just do exactly what the market expects or wants it to do.

But getting way out of whack with informed public sentiment without offering good reasons for doing so is very dangerous.

US Chief Justice Earl Warren – the great liberal reformer who desegregated education, ensured the right to a lawyer in criminal cases, and established the principle of one person one vote – was famously mindful of the Court not getting too far ahead of public opinion.

In Brown v Board of Education, which ruled racially segregated education unlawful, Warren worked hard to ensure a unanimous opinion of the Court. That opinion required desegregation “with all deliberate speed” – a phrase that was justly criticised as allowed desegregation to proceed far too slowly, but ensured that the court wasn’t too far out ahead of the Southern states and allowed them to adapt rather than defy it.

The Reserve Bank’s problem is not getting too far ahead of public opinion, it is lagging too far behind.

The consequences can be similar, though. If the public and the markets lose faith in the Bank as an institution – if it seems radically out of touch – then it will lose it’s ability to persuade and it will risk forced change from the outside.

Forced change is a possibility. Each new government strikes a new agreement with the Reserve Bank governor setting out what it expects of him.

The present one specifies “inflation between 2 per cent and 3 per cent, on average, over time”. If it can be seen that the governor has paid scant regard to the agreement, the new one might make the target more binding, or replace it with a different target.

It’s time to stop waiting

Governor Lowe waiting for wages to tick up without any underlying factor to cause it to happen is like Waiting for Godot. And it’s getting absurd.

He needs a better narrative than “something will turn up”, and he needs to cut rates. Not with all deliberate speed, but fast.

Author

Richard Holden is a Professor of Economics at UNSW.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.