Where Do All the Women Go? Architecture Still has a Gender Equity Problem

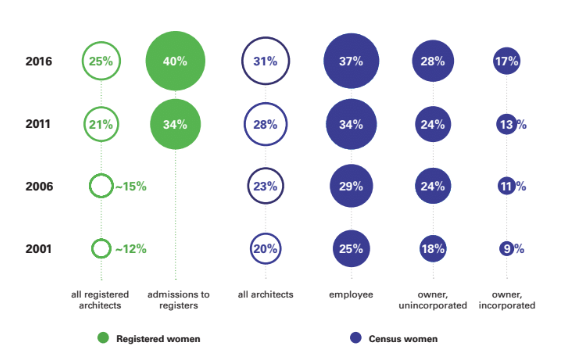

The representation of women at senior levels in architecture is still disappointingly low, despite women now making up 31 per cent of the total architecture population in Australia, according to a new report using Census data.

The report, published by gender equity advocacy group Parlour, explores the participation of women in the traditionally male-dominated architecture field.

And the data provides a pretty bleak story of women’s role in architecture, with “muted” growth of women into senior and more influential roles within the profession.

Since the mid ’90s, women have comprised 40 per cent of all architectural graduates and the number of women in architecture has grown from 20 per cent in 2001 to 31 per cent in 2016. In 2016, women make up one-third of architects in New South Wales and Victoria.

Despite equal numbers of women and men entering, and graduating from, architecture school, attrition metrics measured by Parlour reveal that women are present in strong numbers in the junior ranks of the profession, but disappear from its senior levels.

“There is a distinct fall-off in the numbers of women in architecture as they age,” report author Gill Matthewson says.

“It is this unequal attrition that results in the sluggish growth of women’s numbers and that suggests that gender biases are a contributing factor in women ‘leaving’.”

Related: Indigenous Urban Design ‘Not Just a Moral Choice but a Profitable One’

Since Parlour’s inaugural report in 2012, there’s been a significant uplift in the proportion of women gaining registration, jumping from 34 per cent to 41 per cent.

Matthewson says Parlour has been advising women to register as an important tactic: “because, for many complicated reasons, it is more important for women to have credentials, such as registration, than it is for men”.

Sustained growth in the graduation and registration of women architects is also bolstered by the growth in the number of women who own architecture businesses. In 2001, women comprised just 14 per cent of owners, growing to 21 per cent in 2016.

Nonetheless, the growth in the proportion of women is more sluggish than might be expected from the “flood” of graduates into the profession.

“[This] suggests that gender-based bias impacts more severely upon those in the architecture profession as they age,” Matthewson says.

The slower growth in these metrics suggests that structural and cultural factors continue to disrupt the elevation of women into leadership positions.

“This does not mean that no women are reaching those levels, but rather that if all things were equal, there would be more of them.”

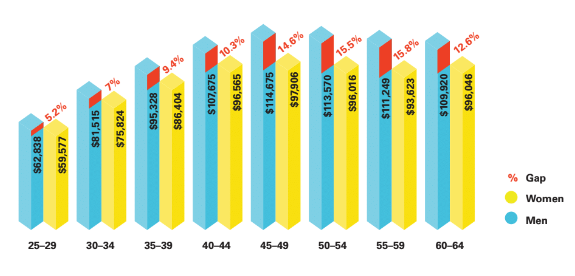

As for pay gaps, there are two patterns that persist. One brings good news: the gap within an age group lessens over time (in 2001 the gap for 35-39 year olds was 16.3% compared to 9.4% in 2016), while the other is more concerning: the older a woman architect gets the wider the pay gap becomes.

Gender pay gap for full time workers in architecture, 2016

A McKinsey report released this month on women in the workplace says companies need to make more decisive action and start “treating gender diversity like the business priority it is” by setting targets and holding leaders accountable for results.

“If we are to see equivalent and serious change in the metrics that currently demonstrate the continuing inequity in the profession, we need more than individual women “doing it for themselves,” as successful as that has been,” Matthewson says.

“The message of the power and importance of equity needs to be activated in every nook and cranny of the architecture profession, individually and collectively.”