Resources

Newsletter

Stay up to date and with the latest news, projects, deals and features.

Subscribe

The summer countdown is ticking towards increased loads of tiny, unsafe airborne particulates in our built and work environments, writes Boon Edam Australia managing director Michael Fisher...

The familiar whiff of smoke from bushfire reduction burns is sending a signal to building and business operators around Australia to prepare for a “new normal” of more airborne hazards affecting our built environment and workplaces this spring and summer.

Large parts of Queensland and the Northern Territory, the south-west of Victoria and south-east of South Australia have been warned by the National Council for Fire and Emergency Services (formerly the Australasian Fire and Emergency Service Authorities Council or AFAC) to expect increased risk in the months ahead.

NSW also reports buildups of fuel such as dried grass, leaves, twigs and dead branches that contribute to risks of outbreaks that can be hard to control once they take hold. Fires such as these send clouds of smoke containing toxic particulates into the growing urban centres of Australia, the most fire-prone country on Earth, where we now have 45,000-60,000 in a “normal” year.

Adding to the load on our lungs this year—and our duty of care to safeguard occupants of buildings and workplaces against lung and heart disease—are loads of particulate matter (PM) emitted directly from sources such as construction sites, unmade road sites, smokestacks and by complex reactions of chemicals such as sulphur dioxide and nitrogen oxide pollutants emitted from power plants, industries and vehicles. [Even clean, green EVs, due to their increased weight, can emit significantly higher levels of particulate matter from tyres].

This increasing prevalence of airborne pollutants was recognised by Safe Work Australia this year with Australia’s new model WHS Regulations, under which persons conducting a business or undertaking must ensure that no person at the workplace is exposed to an airborne contaminant at a level above the exposure standard in the workplace exposure standards for airborne contaminants.

These new workplace exposure limits for airborne contaminants are scheduled to become effective from December 1, 2026, helping to protect Australia’s enviable air quality outside of dramatic spikes such as during 2019-20 fires which burned with unprecedented intensity through a total of 24 million hectares (59 million acres), an area the size of the U.K. They recognise that work processes as well as nature can release dust, gases, fumes, vapours or mists into the air.

These airborne contaminants may be invisible to the human eye, but people who breathe in airborne contaminants at work may be at risk of adverse health effects, including developing occupational lung diseases or heart issues.

So now persons conducting a business or undertaking (PCBUs) must eliminate or minimise risks in the workplace, as far as is reasonably practicable. This includes risks from airborne contaminants in the workplace and ensuring that workers and others at the workplace are not exposed to levels of airborne contaminants above their workplace exposure standard (WES).

Before I discuss how “tight” buildings can assist in controlling risk by excluding contaminants—and not leaking energy and admitting pollution through their front door—let’s look first at the nature of the problem.

Here we are assisted by one of the world’s leading environmental and human health research organisations, the US Environmental Protection agency, the independent agency of the United States government tasked with environmental protection matters, which offers guidance on the nature of PM and how it gets into our air.

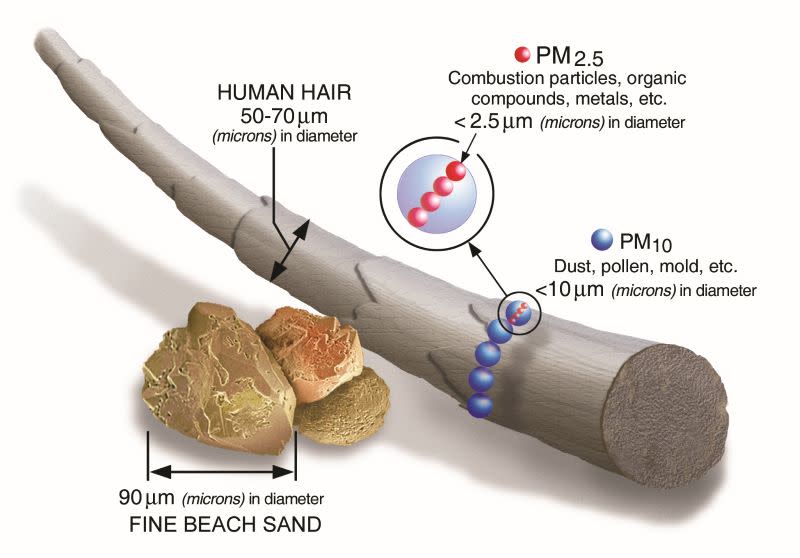

PM stands for particulate matter [also called particle pollution]: the term for a mixture of solid particles and liquid droplets found in the air. Some particles, such as dust, dirt, soot, or smoke [such as our endemic bushfire smoke] are large or dark enough to be seen with the naked eye. Others are so small they can only be detected using an electron microscope.

PM10 : inhalable particles, with diameters that are generally 10 micrometres and smaller; and

PM2.5 : fine inhalable particles, with diameters that are generally 2.5 micrometres and smaller.

How small is 2.5 micrometres? Think about a single hair from your head. The average human hair is about 70 micrometres in diameter—making it 30 times larger than the largest fine particle.

Particulate matter contains microscopic solids or liquid droplets that are so small that they can be inhaled and cause serious health problems. Some particles less than 10 micrometres in diameter can get deep into your lungs and some may even get into your bloodstream. Of these, particles less than 2.5 micrometres in diameter, also known as fine particles or PM2.5, pose the greatest risk to health.

The EPA notes that fine particles are also the main cause of reduced visibility [haze] in treasured national parks and wilderness areas, which, incidentally, is where much of the bushfire smoke in Australia emerged when our capitals were blanketed with it just a few years ago.

Thanks to the EPA, people in the US can use air quality alerts [AirNow alerts] to protect themselves and others when PM reaches harmful levels: Every day the Air Quality Index [AQI] tells inquirers how clean or polluted their outdoor air is, along with associated health effects that may be of concern. The AQI translates air-quality data into numbers and colours that help people understand when to take action to protect their health. That’s how seriously they take it.

Here in Australia, all levels of government play a role in managing the country’s air quality. The Australian Government works with states and territories to improve air quality and reduce people’s exposure to air pollution under the National Clean Air Agreement. The Australian Government takes the lead on issues that need a national approach.

This includes setting national standards and regulating imports of polluting products. States and territories are responsible for air quality in their jurisdictions.

And they do a good job of raising awareness in times of airborne pollutant stress, warning people to stay inside—and particularly cautioning age-care and medical facilities to protect the elderly and infirm, and alerting schools to protect children by keeping them at home or inside.

In doing so, they rightly raise awareness among those of us involved in the built environment that increased particulate pollution is a major public health issue, one that designers, builders, specifiers and mangers need to know about and act upon now, so as to protect their compliance with duty of care. This is particularly so with regards to buildings housing large numbers of employees and visitors, including:

Office buildings

Factories and warehouses

Hotels, hospitality and retail venues

Public buildings. tourist hotspots and transport centres

And particularly health and age-care facilities, schools and universities, which have a particular responsibility to safeguard everyone, but especially the elderly, the sick, the infirm and the very young.

Solutions to this issue are many and varied—each building can involve a mosaic of solutions, not a single silver-bullet solution, which does not exist.

But it is possible to identify areas of strong potential for improvement: and one of the first and most obvious places is to address the issue of particulate penetration [and other airborne hazards] into buildings.

We can take our lead from the EPA and our own health authorities, which warn people at hazardous times to stay inside, close the doors and windows and don’t breathe in this toxic cocktail. It seems pretty obvious, particularly in highly built-up and closed-in highrise and densely packed urban and industrial areas.

Many writers, including myself, have advocated before about the value of “tighter” building envelopes that reduce the ingress of external pollutants, allergens, and moisture in denser urban environments. Besides resulting in healthier outcomes, a tighter energy-efficient building envelope can play a crucial role in reducing the energy demand by regulating the indoor thermal behaviour of the building.

So the reasonable question needs to be asked: why are we still designing buildings with their major entrances [such as sliding and hinged doors] that leak expensive HVAC air every time they open, and lay out the welcome mat for unhealthy toxins including:

Dust and fine particles from vehicle exhausts, workplace boilers, construction sites, and other outdoor activities which find their way indoors through such entrances, as well through windows, doors, and other openings. This fine particulate matter can also get drawn indoors through a building’s HVAC system, where it needs to be efficiently trapped.

Then there are pathogens—viruses (including the coronavirus that causes Covid) and bacteria that can linger on surfaces and in the air, spreading contagious illnesses. These pathogens may be distributed throughout a building by the HVAC system or be recirculated through ductwork. UV light treatments are already used in restaurants, grocery stores, and hospitals to disinfect surfaces and equipment.

But surely the first and most obvious area for improvement is the entrances to buildings, their street-front doors through which contaminants, pollution, natural allergens, bushfire smoke, noise, and ambient heat and cold often pass freely to impose loads on HVAC systems.

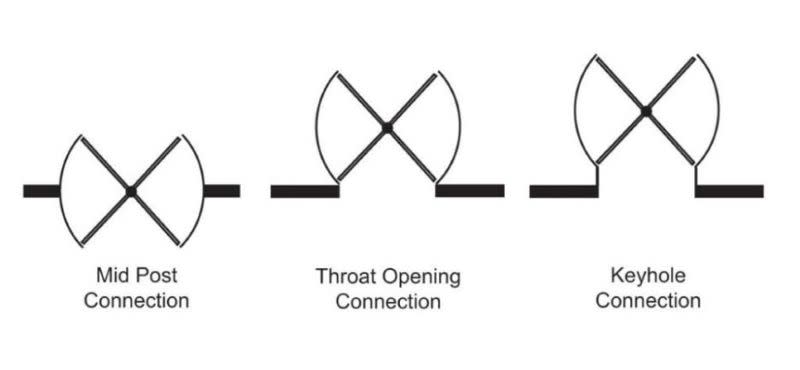

Architectural revolving doors are my particular interest, naturally enough, as the head of the Australasian operation of one of the world’s leading producers of energy-saving architectural revolving doors [the Royal Boon Edam Group, with operations in 27 countries]. My focus is on the role of architectural revolving doors as part of the building envelope, which, as architects and specifiers appreciate, extends across all the building components that separate the indoors from the outdoors, including exterior walls, foundations, roof, windows and doors.

And please understand at the outset that in no way am I suggesting that revolving doors are a total building solution or that they are superior to other door types in every installation. In fact, we do many installations where they are effectively combined with sliding, hinged doors, where internal traffic flow may require this approach [as well as layered security speed gate solutions where these are the most effective people movement solutions in particular locations].

But it is scientifically undeniable that revolving doors offer a “tighter” seal of a building, compared with Australia’s hundreds and thousands of sliding and hinged doors in building entrances in dense urban and industrial locations. In such locations particularly they constantly leak expensively warmed or cooled HVAC air 24/7, or admit into the building outside hot or cold air streams containing particulates, to place greater loads on a building’s HVAC system.

Highly respected Australian companies such as IMB Bank Wollongong are already showing great foresight in this area, and implementing revolving doors at the entrance to their building. IMB installed a Boon Edam Crystal Tourniket all-glass revolving door, which also “lets in an abundance of natural light, making the entire foyer a welcoming space for visitors and employees”, according to IMB’s head of facilities, Greg Dowd.

The always open, always closed energy saving principle of revolving doors has demonstrated globally their comfort and care benefits in healthcare and hospital applications where the maintenance of stable temperatures is important to patient and resident wellbeing.

This scientific fact—the “tightness” functionality of revolving doors – was validated recently by software developed by Boon Edam in partnership with one of the world’s leading technical universities. Delft University of Technology [TU Delft], which ranks in the top 10 engineering and technology best universities in the world. This software is now available throughout Australia, New Zealand, and Papua New Guinea.

We invite readers to review its application to their projects and see how, in these times of high energy costs, they repay RoI faster than ever before, while their always open/always closed functionality acts in a major way as an air lock to exclude toxins, pollutants and health hazards, man-made and natural.

As well as being versatile architectural focal points, revolving doors have been producing healthier, more comfortable, and more energy-efficient outcomes across the building spectrum for nearly as long as Boon Edam has been in business, 150 years. Ongoing drivers internationally of their expanding success [producing a market size estimated at $A1.5 billion in 2024, rising to exceed $A2 billion by 2031] include:

Improving occupational safety standards in new and retrofitted applications

Ensuring optimal space utilisation, particularly in lobby areas

Advancing integration of digital access technologies to enhance traffic flow while allowing for disability access

Preventing unauthorised access in layered digital security applications

Efficiently addressing severe spikes in particulate pollution, especially caused by bushfire in Australia.

My contention is that revolving doors have earned their place to be considered as one of the first and obvious immediate improvements to Australian built and workplace environments that can contribute not only to building Green Star ratings, but also to duty of care obligations in protecting health and safety.

Michael Fisher is managing director of Boon Edam Australia, which is part of the privately owned international Royal Boon Edam group, which provides architectural revolving door and layered security solutions to some of the world’s largest companies, Fortune 500 companies and companies in Australia, New Zealand and Papua New Guinea, including financial, data and telecommunications, federal and state government, hospitality, health and age care, logistics, retail, and distribution facilities.

The Urban Developer is proud to partner with Boon Edam Australia to deliver this article to you. In doing so, we can continue to publish our daily news, information, insights and opinion to you, our valued readers.