Housing Crash ‘Remains Unlikely’: AMP Capital

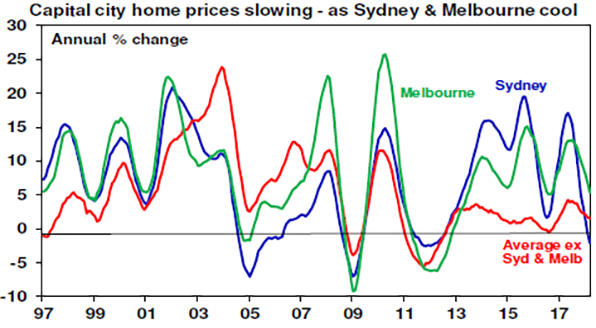

House prices in Australia’s two largest cities are weakening after years of unrelenting growth – between March 2012 and July 2017, the annualised return on Sydney homes was an astonishing 10.7 per cent.

And according to AMP chief economist Shane Oliver median residential property prices in Melbourne and Sydney will likely drop five per cent this year, with further falls in 2019.

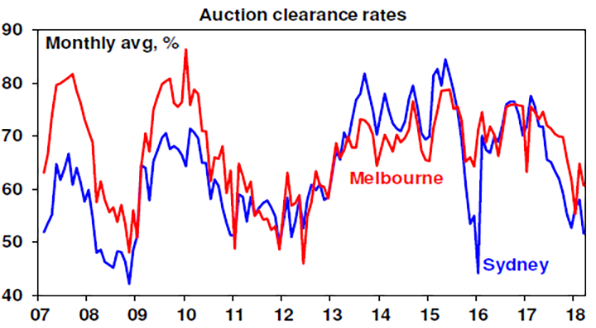

With home prices across Australian capital cities falling 0.2 per cent in March and annual growth spiraling to 0.8 per cent from 11.4 per cent in May last year, is a crash destined to hit the property market?

The signs might be there, but AMP chief economist Shane Oliver said there’s no need yet to bunker down.

“With prices falling in Sydney and Melbourne some see this as the start of a crash.

“While crash calls and stories of mortgage stress are common, they have been repeated endlessly over the last 15 years. But, a crash (say a 20 per cent national average price fall) remains unlikely,” he said.

Related reading: Non-Residential Building Continues to Buoy Australia’s Construction Sector

Oliver pointed out that the real driver of high home prices and their persistence has been that the supply of dwellings has not kept pace with population driven demand.

“Over the last decade annual population growth has averaged about 150,000 above what it was over the decade to the mid-2000s, which would require roughly an extra 50,000 new homes per year.

“While mortgage stress is a risk, there has been a sharp reduction in interest only loans since APRA strengthened lending standards.

“Debt servicing payments as a share of income have actually fallen slightly over the last decade and Census data shows that the share of owner occupier households with a mortgage for which debt servicing is above 30 per cent of income has fallen from 28 per cent in 2011 to around 20 per cent.

Related reading: Slow Apartment Market Weighs on February Building Approvals

“While there has been some deterioration in lending standards it does not appear to be anything like that seen with NINJA (no income, no job, no assets) loans in the US prior to the GFC,” he said.

Real capital city house prices are 27 per cent above their long-term trend and are at the high end of OECD countries in terms of the ratio of prices to income and rents.

Prices relative to income since the mid-1990s have also surged, along with the ratio of household debt to income, and a long period of strong prices and low mortgage rates has caused some deterioration in lending standards.

The share of new interest-only loans reportedly reached around 45 per cent in 2015 while concerns appeared about the reliability of borrowers’ income and living expense assessments when they take out loans.

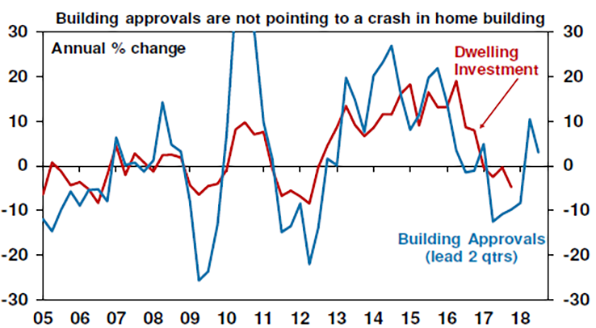

“A slowdown in the housing cycle can affect the broader economy via slowing dwelling construction, negative wealth effects on consumer spending and via the banks if mortgage defaults rise,” Oliver said.

Housing construction slowed again last month, as commercial construction and infrastructure work experience robust levels of activity.

“However, as things currently stand the drag from housing construction is likely to be minimal – building approvals don’t point to a collapse in new and it looks like alterations and additions will rise, negative wealth effects will weigh on consumers but not dramatically … and in the absence of a property price crash the impact on the banks will be manageable.”

‘The worst has passed’

Oliver’s outlook comes after ANZ economists lowered their housing price expectations for 2018.

ANZ said that weaker sentiment had primarily caused softening prices in 2017 and that the worst of the correction in the market had passed.

Property researcher CoreLogic said last week that the Sydney price falls were likely nearing the bottom. The fall in home values was slighter than expected, with the Australian housing marketing showing every sign of recording a “soft landing” after prices peaked in September 2017.